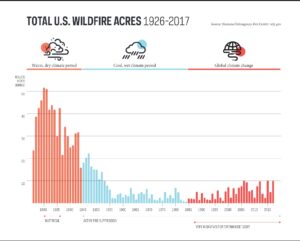

The influence of fire suppression is exaggerated. The idea that there was a “hundred years” of fire suppression ignores the fact that in the early 1920s and 1930s as much as 50 million acres burned annually. Furthermore, climate controls fires, as indicated by the cool, moist decades between the 1940s-1980s.

With large fires still raging around the West, we can all feel empathy for those who lost their homes and even entire communities and all of us suffering from the smoke.

Still, there is a lot of smoke and mirrors about the blazes and their cause.

The timber industry, Forest Service, and forestry schools are quick to suggest that logging can reduce large blazes. Rushing to log forests will not solve the problem; indeed, it can worsen it. More subsidized logging takes funds away from solutions that can protect communities.

First, we must address many of the misguided information.

1. Climate change is driving much of the massive blazes we are experiencing in the West. Higher daily temperatures, extreme drought, low humidity, and high winds resulting from climate change exacerbate vegetation’s flammability. Severe fire weather is driving large blazes, not fuels.

Wind drives all large blazes. Without wind, fires don’t spread fast or far.

2. The idea that Indian burning kept fuels low, hence prevented large stand replacement blazes, is an exaggeration. The fire intervals recorded in charcoal studies and other methods have shown that large fires were always occurring before the advent of Euro American occupation.

3. You can only get a massive fire when the weather conditions are favorable. It doesn’t matter who or what is the source of ignitions. Indians could not burn much of the landscape because most of the landscape does not burn unless you have extreme fire weather conditions—which do not occur in most years.

4. The majority of plant communities in the West have long “intervals” of hundreds of years between significant blazes. The Douglas fir forests on the west slope of the Cascades now burning in Oregon tend to have natural fire intervals of 300-500 years. Fire suppression has not altered the natural fire cycle at all.

Lush old growth Douglas Fir forest Willamette NF, Oregon. Such forests burn on intervals of hundreds of years. Photo by George Wuerthner.

Most plant communities, including lodgepole pine, aspen, sagebrush, juniper, high elevation fir forests, and so on tend to experience fires hundreds of years apart. During this period, they are accumulating fuels, but that is the natural consequence of their ecology, not fire suppression.

Consider that the 1910 Burn of Idaho and Montana that charred over 3.5 million acres occurred long before “active fire suppression.”

5. High severity fires do not destroy forests. They rejuvenate them. Large fires create much-needed habitat for numerous species. Some studies suggest up to 2/3 of all wildlife species depend on the snag habitat and down logs that result from such blazes.

Snags and down wood are biological legacies critical to healthy forest ecosystems. Photo by George Wuerthner .

6. Winds are the driving force in all large fires. Over the past three decades, I’ve traveled all over the West to view the aftermath of larger blazes in New Mexico, Colorado, Idaho, Washington, Nevada, Wyoming, Montana, Oregon, and California. In every instance, with no exceptions, high winds were the essential and critical variable.

When you have high winds, it blows embers over and through any “fuel reduction” projects. That is why fires like the 2017 Eagle Fire in Oregon was able to cross a mile and a half of the Columbia River to ignite fires in Washington. Many other fires are crossing 16 lane freeways, clearcuts, and other areas with little or no “fuel.” The idea that we can preclude large fires by more “active forest management” is pure delusion.

Clearcut and “active forest management” on Willamette NF where massive wildfires are currently burning. Photo by George Wuerthner.

7. Indeed, active forest management can contribute to more massive and more severe fires because it opens up the forest to greater drying and more wind penetration. One recent study reviewed 1500 fires around the West and found the highest severity blazes occurred in areas with “active forest management” while protected landscapes like wilderness areas where presumably fuels were higher, burned less intensely.

This google earth photo shows the massive clearcuts on the western slope of the Cascades along the Mckenzie River where one of the large blazes is burning. Obviously “active forest management” has not slowed the fire spread.

Plus, after logging, you enhance the growth of shrubs, grasses, and small trees, which are the fine fuels that carry fires. Removing large trees as advocated by the timber industry is a false solution since large trees do not readily burn—instead is it is the small fuels like needles, small branches, and cones, which are the primary fuel for fires. That is why you have snags left after a fire—the large boles do not burn efficiently.

In many cases, forest management has increased the fire frequency, not reduced it. There is a direct correlation between roads (which are built to log the forest) and an increase in human ignitions.

8. Much of what is burning in the massive California fires and elsewhere in the West is not forested, but chaparral, grasslands, sagebrush, and other non-forested habitats. So “active forest management” would have no influence upon much of the acreage currently in flames.

Much of the acreage burned annually in California is chaparral as seen here on the Cleveland NF in southern California. Photo by George Wuerthner.

9. We cannot preclude large fires through forest management, but we can reduce the impacts on humans. An emphasis on reducing communities’ flammability, planning escape routes, burying power lines, and other proven measures can reduce human suffering.

Wind topples trees on to powerlines causing many blazes. Instead of spending money on logging forests, we could redirect towards reducing igntions by burying powerlines. This is near Bend, Oregon. Photo by George Wuerthner.

10. The ultimate cause of these massive conflagrations is climate change. We need to address the causes of global climate change and make this a national priority.