High-powered shootouts are not unusual in Brazil. Despite tighter gun regulations than the U.S., in the poorer neighborhoods of many Brazilian cities, armed gangs and police trade fire with high-caliber assault rifles, machine guns, pistols, and sometimes even grenades and rocket launchers. Rio averages 24 shootouts per day. Large hours-long gun battles often don’t even make the headlines. Yet the shootouts leave a mark: piles of dead bodies.

Where, though, are all of these bullets coming from? The ammunition comes from just about everywhere.

Our analyses of the bullet shells were conducted in exclusive partnership with the Brazilian NGO Instituto Sou da Paz and the Swiss research group Small Arms Survey, who identified the domestic and imported capsules, respectively.

The story told by this sample is clear-cut: In Rio’s armed conflicts, the costs are borne locally by society’s poorest residents, but the responsibility — and the profits — are spread across the globe.

Brazilian Bullets

None of the shootings officially featured the participation of the Federal Police — which had bought this batch of ammunition in 2006. Brazil’s Federal Police is roughly comparable to the Federal Bureau of Investigations in the U.S. Like the FBI, the Federal Police very rarely participate in shootouts. Instead, police-involved street battles usually engage state-level forces called the Military Police, who do the bulk of street-level law enforcement. However, in 2018, in an extraordinary measure, the Brazilian Army assumed command of Rio’s state security apparatus for nearly 11 months. Soldiers conducted operations in some neighborhoods, sometimes side-by-side with Rio’s state-level police.

As with the casings collected from Complexo do Alemão, the Franco assassination, and the Osasco massacre, most of the bullet casings we collected — 94 out of 137 shells — were from shootouts in which neither the police nor the military were involved. Only 43 were found in areas where a police presence was reported on the day of the confrontation. The police did not respond to The Intercept’s inquiries and the military only acknowledged one official operation in the neighborhoods we surveyed during the hundred days we collected shells.

Almost all the ammo we collected was sold with restrictions designating it to police and military use — including some that even the police are only supposed to use under limited circumstances.

Of the 94 Brazilian-made bullet casings in the sample, it was possible to identify the original batch number of 52 of them. Of those, however, we were only able to identify the original purchaser in four cases, because those batches were involved in an investigation by the Public Prosecutor’s Office of the Brazilian state of Paraíba. (In response to public records requests, multiple government agencies said information related to the ammunition batches was sensitive or classified.)

One bullet whose origins we were able to identify was fired on July 3, 2018, during a gunfight between the police and drug traffickers from a gang called the Red Command. The shootout took place in the Manguinhos favela in northern Rio. The bullet came from a batch numbered BNS23, purchased by the Brazilian Navy in 2007 — though the Navy did not participate in the shootout.

BNS23 was the largest batch of ammunition ever produced by CBC — more than 19 million units. The extraordinary size of batches like BNS23 represents one of the top difficulties for tracking bullets in Brazil. Ordinarily, the military purchases small arms ammunition in batches of 10,000 units, which itself is too large to allow for tracking. A recent official recommendation by the Public Prosecutor’s Office suggested lowering the maximum size of ammo batches, but without specifying a number. The 19 million units of ammunition shipped in batch BNS23 exceeds the limits established by law.

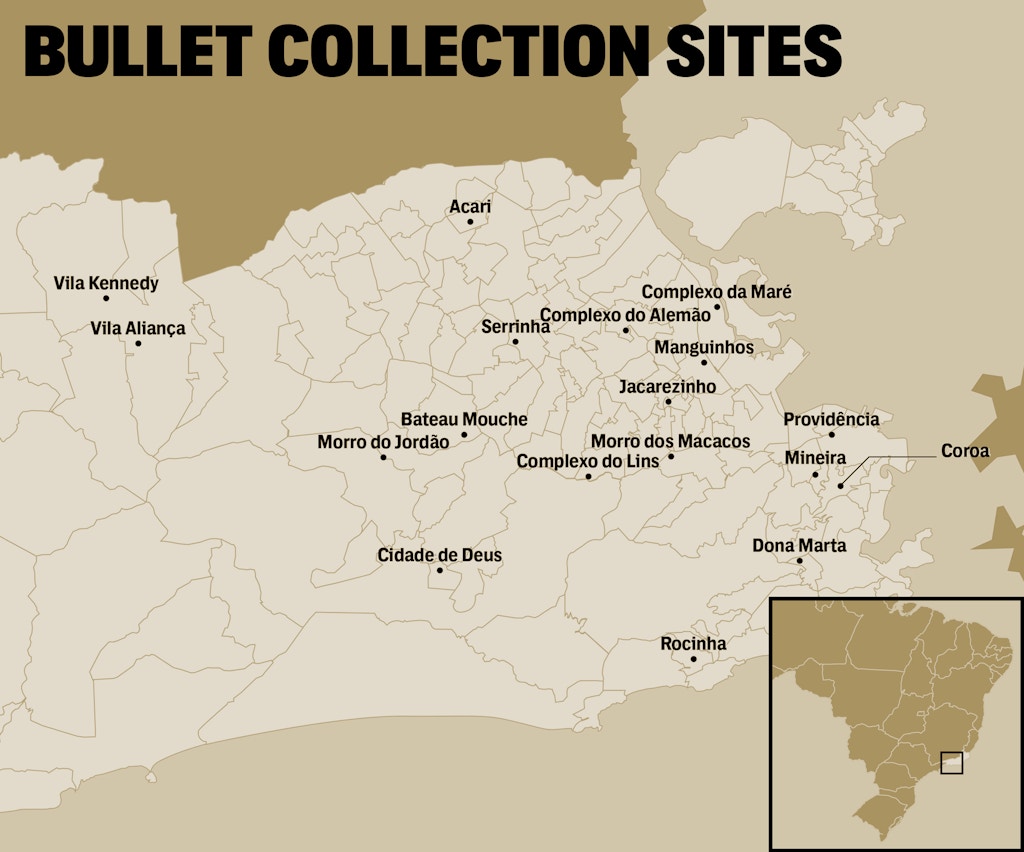

Map: The Intercept Brasil

Among the CBC casings collected was a 7.62×39 mm round with markings that indicated it was produced for export — ammo that is not supposed to be sold in Brazil, even to the military. In response to inquiries, CBC said, “7.62x39mm MRP / CBC ammunition is not currently manufactured or marketed by CBC.” The company said the ammo was last sold in 2005. Thirteen years later, on July 11, 2018, it was collected by our team in the Bateau Mouche favela, 10 miles to the west of Maré.

On map, from left to right: United States (22); Brazil (94); Belgium (1); Bosnia (1); Czech Republic (2); Russia (14); China (2). One shell was of an unidentifiable origin.Graphic/Map: The Intercept Brasil

Ammo From Abroad

The U.S. wasn’t alone: We found bullet casings from Belgium, China, Russia, the former Yugoslavia, and the Czech Republic.

Not far from the Belgian bullet casing, we picked up a .223 Remington-style round manufactured by the Chinese defense contractor Norinco. The cartridge was designed in 1957 to be used in American-made AR-15 semi-automatic rifles. This one was made in 1995.

All of the retrieved .308 shells featured a golden primer and a silver casing, suggesting that the shells had been used, then had new bullets loaded into them. While Brazilian law allows for refills by sharpshooters, recreational hunters, shooting clubs and federations, weapons industries, and similar entities, they must be granted permits by the Army. These same organizations also may be granted permission to import certain weapons and ammunition. Another possibility, therefore, is that the bullet casings we found may have been diverted from one of these entities.

We retrieved a 7.62×39 mm bullet casing, made for use in AK-47s, at a scrap yard in Manguinhos on July 20, 2018. On that same day, a shootout between drug traffickers from the Red Command and the police left one civilian dead and two others wounded. The cartridge is stamped with “??”, an identifier for the Igman Zavod company (now Igman d.d. Konjic) and “1978,” indicating the year it was manufactured. According to U.N. data, Brazil has not reported the import of any Bosnian arms in the last decade and only $15,163 in goods in the decade prior.

Josip Broz Tito, Yugoslavia’s decadeslong military dictator, was a key figure in the Cold War-era Non-Aligned Movement. As Brazil was one of the countries with observer status in the movement, Yugoslav law permitted that ammunition could have been legally exported to Brazil prior to 1992, but we were unable to locate any such records showing that it had been.

Photo: Mauro Pimentel/AFP via Getty Images

How Not to Track Munitions

We requested information about the more than 50 other batches of ammo that we identified but could not track down any purchase records despite multiple requests to CBC, the Army Command, the Ministry of Justice and Public Safety, and Comptroller General’s Office. All of these entities denied access to the relevant information, claiming it was either confidential or outside the scope of their competency.

Graphic: The Intercept Brasil

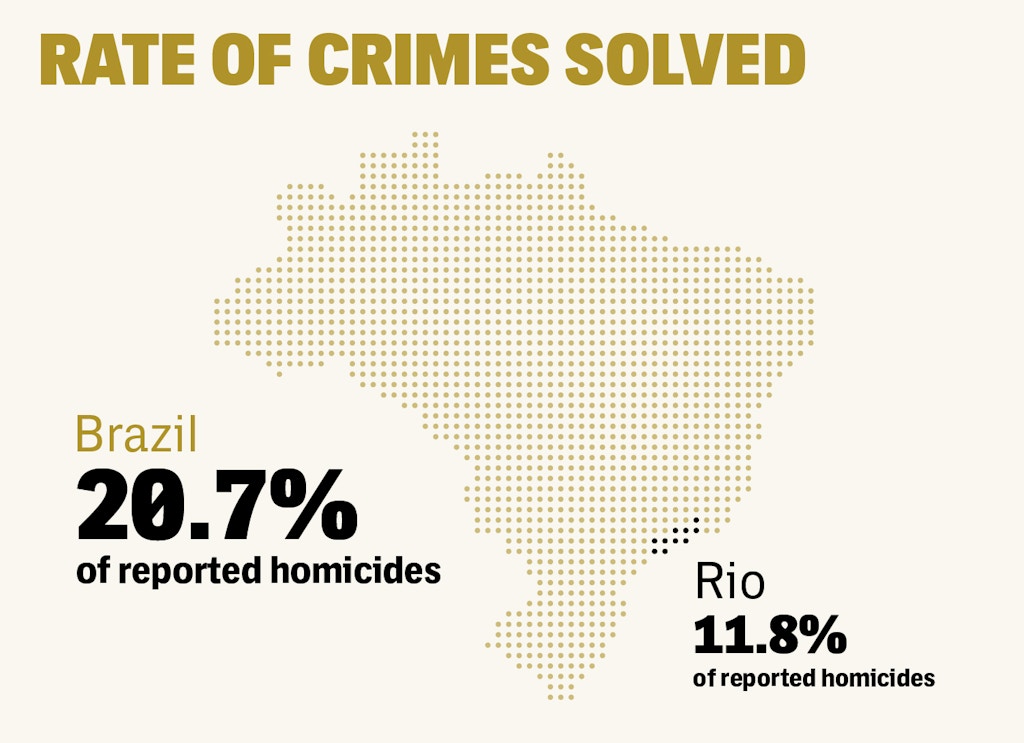

Perhaps it is no coincidence that a country with poor arms controls and transparency also happens to have an out of control homicide problem — 51,589 dead in 2018 — and a dismally low rate of solved homicide cases, about 20.7 percent nationwide and an abysmal 11.8 percent in Rio alone.

These numbers could be improved by a handful of simple measures. The legislation and guidelines already exist: the Statute of Disarmament from 2003, Army Decree 16-D LOG from 2004, and the U.N. Office for Disarmament Affairs’ guideline on arms tracing, IATG 03.50.

Either the Army failed to properly oversee millions of ammunition units, or an arms manufacturer flouted rules without consequences.

Together, these statutes establish that ammunitions manufacturers must stamp the bottom of each shell with the batch number of each shipment and the name of the buyer; that each batch be limited to a maximum of 10,000 units; and that each nation create an integrated system to track weapons supplies among different public safety agencies, covering both the issuing and receipt of ammunition between manufacturers and buyers. The companies and government agencies must also make all of these records available to the public.

CBC, Brazil’s main firearms and ammunition manufacturer, told us that their “labeling involves three letters and two numbers stamped on the butt of the cartridge, which will uniquely identify the batch and purchaser of each product.” Since the company does not provide these details to anyone besides the Army, however, these stamps are of little help to the public. They stand only as a sort of secret code.

On the rule of a maximum of 10,000 units per batch, CBC replied to our inquiries that this quantity refers to the limit for partitioning each batch. “CBC complies with clauses I through VII of article 6 of Law 10.826 of 2003, in accord with the quantity established in contracts and authorizations determined by the Brazilian Army,” the company said. Meanwhile, the Armed Forces take a different view: The limit of 10,000 units per batch “holds for any purchase, specifically relevant for traceable ammunition, whether sold to public safety agents or to the Armed Forces.”

In other words, either the Army — which is responsible for monitoring the rules they established — failed to properly oversee millions of ammunition units, or CBC flouted these rules without consequences. More likely, both explanations are simultaneously true. The information we obtained from the Army through the Access to Public Information Act shows that, in the eight years between 2010 and 2018, the number of cartridges imprinted with manufacturer information has actually decreased, plummeting from 43 to 26 percent.

In the past six years, more than 960,000 rounds of ammo have been seized by authorities in Rio de Janeiro. In 2018 alone, that number was 212,000. Given the poor state of oversight of legal, domestic ammunition, one can only imagine the situation with imported and contraband bullets.

Meanwhile, 1,338 people were murdered in Rio de Janeiro in 2018.

Translation: Andrew Nevins

Cecilia Olliveira | Radio Free (2019-12-16T04:01:19+00:00) We Scoured the Streets of Rio de Janeiro After Gun Fights. Here’s the Story the Bullet Shells Tell.. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2019/12/16/we-scoured-the-streets-of-rio-de-janeiro-after-gun-fights-heres-the-story-the-bullet-shells-tell/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.