This article is part of a dossier in partnership between SyriaUntold and openDemocracy’s North Africa, West Asia page, exploring the emerging post-2011 Syrian cinema; its politics, production challenges, censorship, viewership, and where it may be heading next.

In recent years, film documentaries seem like the most controversial form of Syrian artwork. They are divisive both for the Syrian regime’s supporters and its opponents, but also among the regime’s opponents themselves about films produced by directors opposing the Syrian regime. More than eight years after the eruption of the Syrian uprising, this continuous debate over several Syrian documentaries raises questions about the focus of the dispute on this genre, and the nature of the audience of the Syrian documentary film today.

The Syrians and the Oscars

Around the time of its nomination for the Oscar for best documentary, the leak of the Syrian documentary “Fathers and Sons” earlier this year provoked a controversy in some Syrian circles. The director of the film, Talal Derki, went to a village in the countryside of the Syrian city of Idlib that was under the control of various Islamic organizations. Disguised as a director sympathetic to jihadi thoughts, he spent some time in the house of the family of Abu Osama, a Salafi jihadist. He then made a film condemning Abu Osama and his ideas, after filming his family and children.

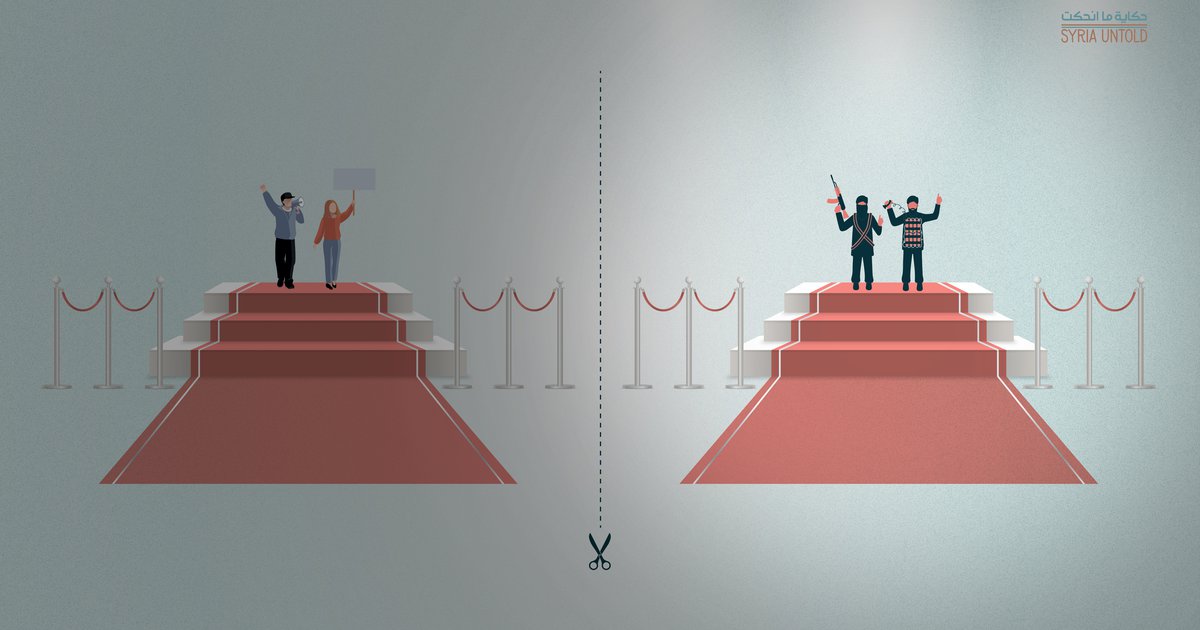

After the film was leaked and seen by a large number of Syrians, part of the Syrian public opinion considered that the Oscar nomination of the film was due to the filmmakers’ positions. The latter would have benefited from the accordance of his ideas with the counter-terrorism strategy prioritised and adopted by different US administrations. In the Syrian case, this means prioritising the fight against potential extremist groups in Idlib, to the detriment of pressure on the Syrian regime to bring about political change in the devastated country.

What concerns us in the debate about the film “Fathers and Sons” is not the merits of opinions supporting or opposing the film’s approach. It is rather interesting to look at the problematic relationship between the Syrian audience and Syrian documentary films, whether in regards to the angry reactions to some leaked movies, or the total absence of any reaction as in the case of most Syrian movies.

European centrality

Despite the fame and commercial success of many Syrian documentaries after the revolution, the dilemma of the Syrian documentary film and how to reach the Syrian public is not a new one. It is rather an old issue related, on the one hand, to the stifling political repression, and on the other, to the absence of broadcasting or screening options that allow the producers to recover some of their costs, such as cinemas or TV channels, which can buy television screening rights.

According to the Syrian director and documentary producer Guevara Nemer, the problem of distributing Syrian documentaries cannot be reduced to a prior tendency of filmmakers to ignore the Syrian audience, presuming that they target mainly European or Western audiences. The problem predates the Arab uprisings and is related to the structure of the production market and the distribution of documentary films.

That being said, European countries represent the largest market for the documentary production, display and distribution. This is due to the existence of various forms of financial support for documentary films in Europe, in addition to notable festivals that ease the way for films into the markets, as well as on to television channels that may produce or buy documentary rights such as Arte, Channel 4, etc.

The disadvantage of mass production

According to Nemer, distribution of big productions doesn’t depend necessary on the director, but rather on distributors who are responsible for selling the film to local distributors. This complex distribution process, especially in the case of big budget films, which is the case with recent Syrian documentaries, prevents the director in one way or another from selecting the type of audience that the film can reach, unless the director had already required in the production contract to screen the film on special occasions, a situation that usually occurs with modest films.

Since the success of a documentary depends on the length of its lifetime in the festival circuit and exclusive screenings, the least funded and successful films by the market standards are the most likely to eventually access free online viewing, as they have lost their chances of being shown in theatres or television. This means that small-budget films and the least commercialised ones are the most likely to access the average Syrian viewer through the Internet.

Traditions of ambiguity

In addition to the structure of the distribution market today, it seems that the problematic relationship between the Syrian public and documentaries is due to the deep reliance of current Syrian documentaries on the lives of the Syrians. Unlike other artworks such as literature and imaginary cinema, in which the imaginary space helps create a safe distance with reality, documentaries focus on the lives of real Syrian individuals. Their stories are transmitted on screen, sometimes without major changes. At the same time, the current production and distribution market increases the distance between documentaries and the Syrian audience.

This ambiguous relationship is also amplified with, what I suggest calling, the “traditions of ambiguity”. These traditions are much more related to the artistic choices of Syrian filmmakers than to the structure of the market. It seems that the renowned directors of the current generation of Syrian filmmakers have inherited these traditions from the late Omar Amiralay, the most famous Syrian documentary director.

Amiralay, whose films were highly politicized, adopted in one of his most famous movies “A Flood in Baath Country” an ambiguous relationship with the Syrians he portrayed. He filmed fearful individuals and ideologues who repeated throughout the film slogans of the ruling Baath Party in Syria. The director then reformulated these scenes in the editing process adding his personal critical comments on the relationship between these individuals, the State and the repression it imposes on them. This creates a tripartite relationship: The State, the oppressed Syrians, and the critical director who reveals this relationship by portraying these Syrians as ideological voices, and not as individuals with complex sensitivities and behaviours.

This same approach has been repeated recently in the film “of Fathers and Sons”, and to a lesser extent in other films such as “The Taste of Cement” and “Return to Homs”. In these documentaries, the temporary and non-intimate shooting of the film’s characters imposes a superficial relationship with these characters, during which they repeat general political slogans. It is the case of the Salafist discourse in “Fathers and Sons”; the revolutionary discourse of the late Abdul Basit al-Sarout in “The Return to Homs”; or the discourse of unhappiness and lack of hope of Syrian workers in “The Taste of Cement”.

Whether the reason for the distance between the Syrian documentary and its audience is related to the structure of the market that excludes the public, or the philosophy of some filmmakers in making films that circumvent the intentions of some of the Syrians, the result remains a quasi-absent relationship between the Syrian documentary and its public, both inside and outside Syria. It doesn’t seem that the coming years will be able to solve this problem, given the widening gap between inside and outside Syria on the one hand, and the decline of the global interest in the Syrian case on the other.

*Translated by Diana Abbany