Immigration lawyers in New York City already had their hands full. In the weeks before the world was gripped by the coronavirus pandemic, reports were coming in from across the city and surrounding areas of increasingly aggressive immigration arrests. In addition to some of their well-known tactics — showing up at homes early in the morning, arresting people on their way to court, and passing themselves off as New York City cops — teams of Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers were turning up in larger numbers and their operations seemed to be taking on a more militarized feel.

Tensions exploded in February, when a team of ICE officers attempting to arrest an undocumented construction worker in south Brooklyn shot the son of the man’s girlfriend in the face. Hundreds of people protested in the streets. Democratic lawmakers demanded answers. A month later, a viral photo circulated of an ICE officer standing in a Bronx hallway wearing tactical gear with a rifle propped against his shoulder. Community members began reporting Border Patrol agents joining arrest operations deep in residential communities.

The reason for the escalation was no mystery. Heading into an election year in which the White House would no doubt tout its immigration crackdowns, the Trump administration was in the midst of a blitz, targeting so-called sanctuary cities with ramped-up surveillance and enforcement in a 10-month initiative dubbed “Operation Palladium.”

But as ICE’s intensified and politicized operations were unfolding in the early months of 2020, the coronavirus was spreading.

By mid-March, it was clear that New York’s experience of the virus would be a painful one, with estimated death tolls running into the tens of thousands. And while it was evident from recent history that ICE’s network of jails and detention centers were woefully unprepared to handle a highly contagious medical emergency, ICE continued to fill those spaces with human bodies, at times from the communities hardest hit by the coronavirus.

Earlier this month, a day before the governor of New York declared a containment area around the New York suburb of New Rochelle, where the coronavirus was spreading rapidly, ICE sent a team into the community and arrested a man in front of his wife and two young children.

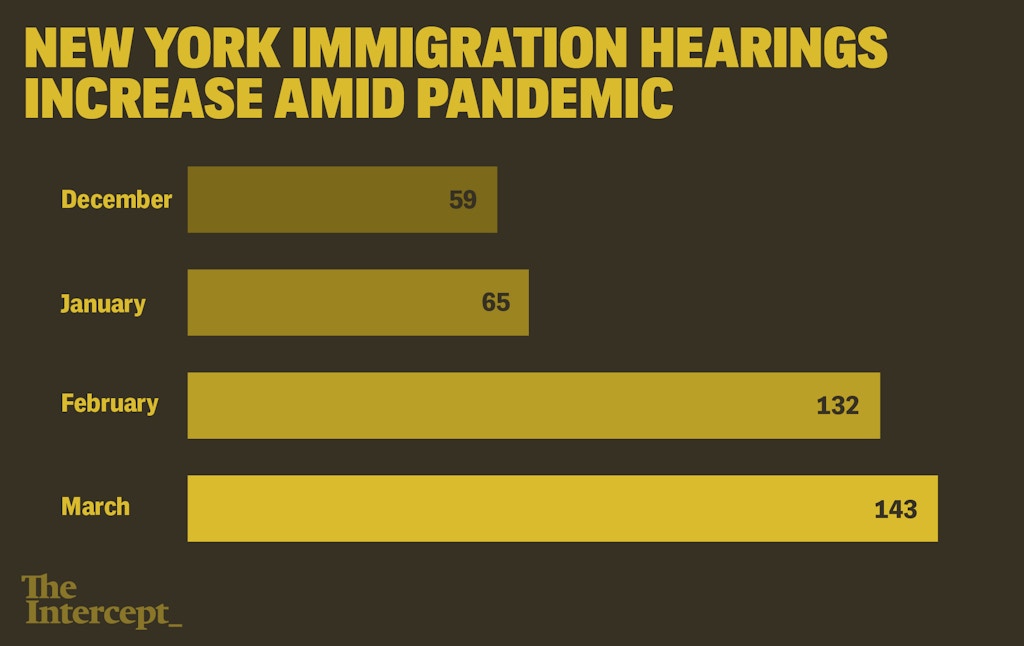

The arrest was one of many. In a review of nearly four months of immigration court records in New York City, The Intercept uncovered a significant spike in immigration arrests following the launch of the Trump administration’s crackdown, with initial court appearances of individuals in detention in February and March more than double what they were in December and January.

Nationwide, the number of people in ICE custody has grown by more than 700 people in the last week, according to the agency’s website, marking the highest total in nearly a year.

“I think that people are going to die, and I think that ICE is treating that as if it’s almost a given, as opposed to something that they can really reduce.”

ICE’s ramped-up enforcement in early 2020 came as officials at the highest levels of the federal government received increasingly dire warnings about the impact the coronavirus would have on the country. With confirmed coronavirus infections at three of the jails that feed into New York City’s immigration court, and hunger strikes now unfolding at each of those locations, immigration attorneys in New York say that ICE’s operations made an already dangerous public health situation considerably worse.

“In January we could just feel it,” Andrea Sáenz, attorney-in-charge at the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project, told The Intercept. Calls were flooding in from around the city of arrests that would have been unlikely just a few weeks earlier. “It was very obvious.”

Facing a barrage of criticism last week, ICE said it would begin exercising discretion in its arrests, focusing on individuals who are “subject to mandatory detention” or present “public safety risks.” The move reportedly landed the head of ICE, a diehard enforcement hawk who once described facilities for detained immigrant children as “summer camps,” in “deep shit” with top DHS and White House officials. The following morning, acting DHS Deputy Secretary Ken Cuccinelli attempted to walk back the shift. According to Sáenz, ICE was continuing to make arrests in the New York City area “literally up through the morning of March 18 — the day that that announcement came out.”

ICE has offered no indication of plans to release any of the nearly 40,000 people currently in its custody, despite its legal authority to do so at any time. “There has been no policy decision announced at this time,” Danielle Bennett, a spokesperson for the agency, said in an email to The Intercept. Bennett added that “ICE makes custody determinations every day,” which can involve the release of detainees, alternatives to detention, and other monitoring programs. While Bennett declined to discuss the status of Operation Palladium specifically, citing “law enforcement sensitivities and officer safety,” she acknowledged that “most certainly the pandemic changed our operational plans and likely will result in fewer arrests.”

“Are operations still in effect as planned?” she wrote. “Certainly not.”

With the coronavirus sweeping the country, the risks immigrants in detention face cannot be overstated, argued Margo Schlanger, a law professor at the University of Michigan and former top civil rights official at the Department of Homeland Security. “I haven’t seen any sign that ICE is taking seriously enough its constitutional and humanitarian obligations toward the people in its custody,” Schlanger told The Intercept. “I think that people are going to die, and I think that ICE is treating that as if it’s almost a given, as opposed to something that they can really reduce — and I think that’s appalling.”

For the advocates working to get people out of detention in the New York area, where the presence of the coronavirus in detention centers recently became a confirmed reality, the current moment is as critical as any in recent memory.

Six days after President Donald Trump declared that the spread of the coronavirus was a national emergency, which came 14 days after he called it a “hoax,” Sáenz found herself in something akin to legal triage-mode. “There are thousands of people in ICE detention who could be released right now and aren’t, and they include a lot of high-risk people who are going to get coronavirus because they’re there and are going to get really sick and die,” she said at the time. “That’s the No. 1 thing. The No. 2 thing is that ICE enforcement is continuing in the middle of a pandemic.”

As the leading organization providing free legal representation to low-income immigrants facing deportation in New York City, the NYIFUP, which includes attorneys from the Legal Aid Society, Brooklyn Defender Services, and the Bronx Defenders, has been thrust onto the front lines of a swift-moving and rapidly expanding crisis. When we first spoke last week, Sáenz and her colleagues were working around the clock to get clients out of four regional jails that contract with ICE: the Orange County Correctional Facility in Goshen, New York, the Bergen County Jail in Hackensack, New Jersey, the Hudson County Correctional Facility in Kearny, New Jersey, and the Essex County Correctional Facility in Newark, New Jersey.

“If we were to be infected I am sure everyone would rather die on the outside with our families than in here.”

The four facilities funnel people in custody to an immigration court in Manhattan. While their purposes are the same, each of the jails seemed to have its own evolving protocols for responding to the spreading virus, the lawyers soon found. This presented an enormous challenge, Sáenz explained, one that was exacerbated by ICE’s tendency to act with the minimum amount of transparency possible. “We are having to keep up every single day with the state of visitation and conditions and phone calls on all of these jails,” she said. “It’s changed every day.”

The limited information the lawyers were receiving was disturbing. Lack of access to the critical supplies needed to have any hope of warding off a deadly virus — things like soap and hand sanitizer — appeared widespread. In Hudson County, a man described covering the jail’s phone with a sock in order to make calls. Another said he was instructed to save the water in his toilet, causing it to fill with piss and shit. Another said there was no way to call for medical attention. In Orange County, people locked in the jail told lawyers that hand sanitizer had been prohibited as contraband, and that guards who had it were using it to taunt those in custody. In Bergen County, a woman said 30 people were moved to solitary confinement and told they would stay there “until the coronavirus is under control.” A man described hearing new arrivals weeping in isolation.

Though each had its own set of problems, Sáenz was worried about two of the jails in particular. “Right now, I’m the most concerned about Hudson and Bergen,” she said, explaining that clients at the New Jersey jails reported being moved from dorm-like facilities to cells, where they were locked up for most of the day with one other person. Sáenz’s concerns were well-founded; less than 24 hours later, news broke that a corrections officer at Bergen County had tested positive for Covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus.

Signs of a potential humanitarian emergency continued to mount in the days that followed. In Essex County, an entire unit of people in detention went on hunger strike to demand their release. “This coronavirus is getting out of control and if we were to be infected I am sure everyone would rather die on the outside with our families than in here,” one of the hunger strikers said a statement. Shortly after the statement appeared online, word came that a member of ICE’s medical team at the Elizabeth Detention Center in New Jersey had also tested positive for the coronavirus.

By the end of the week, hunger strikes were unfolding at three of the four jails Sáenz and her colleagues were focused on.

Photo: Mel Evans/AP

Trump’s Agenda

The population of detained immigrants now at risk of a coronavirus outbreak did not form in a vacuum, and in New York City the path that led to the current crisis is bound up in the politics of the president.

For Trump and the advisers who shape his immigration agenda, filling detention centers to fuel the nation’s deportation pipeline has been an organizing principle from week one. Five days into his presidency, Trump signed a critical executive order doing away with Obama-era enforcement priorities designed to focus ICE’s resources on individuals who presented a threat a public safety, and away from people with longstanding ties to the country, or whose only troubles with the government might be civil immigration violations.

With the stroke of a pen, virtually all of the nation’s nearly 11 million undocumented immigrants became fair game for ICE to arrest and deport. Those deportations could be happening, the administration told its supporters, if not for a key impediment: so-called sanctuary cities.

The anti-sanctuary city campaign has been a mainstay of Trump’s presidency and there was no reason to believe 2020 would be any different, especially with the administration fighting to hold onto power. While there is no legal definition of such jurisdictions, the term is typically used to describe a place where local law enforcement has drawn some kind of line with ICE — often revolving around holding people in local jails — on the degree of support they will provide. If the president’s goals are to be achieved, the White House argues, then these rogue cities must be brought to heel.

Trump and his top immigration officials have long cast New York City in particular as a key problem area, a place where ICE’s work necessarily assumes a riskier edge because the president’s political opponents make it so.

As the White House shifted into election mode, it quickly became clear that ICE intended to turn up the pressure.

Home to roughly 3 million immigrants, a third of whom are undocumented or live in families where immigration status is mixed, as well as a mayor who considers himself an anti-Trump warrior, New York City has been a talking point in rhetorical war over immigration enforcement in the Trump era. On the ground, the battle is more real.

In a report released in January examining local enforcement under Trump, New York City immigration officials noted a nearly 300 percent increase in the arrests of individuals with no criminal record in the five boroughs compared to the final year of the Obama administration. The staggering jump is just one metric by which to measure the changing face of immigration enforcement in New York City. Advocates have also charted a 1,700 percent increase in ICE’s use of courthouse arrests, wherein targets are taken into custody as they appear for court dates on matters unrelated to immigration.

The fight in New York City has pitted ICE against one of the most formidable legal advocacy communities in the country. Through the city-funded NYIFUP, New York City was the first in the country to provide sustained pro bono legal defense to indigent immigrants facing deportation (unlike the criminal justice system, the immigration system does not guarantee access to a lawyer).

As the White House shifted into election mode earlier this year, it quickly became clear that ICE intended to turn up the pressure. Echoing earlier comments made by Matthew T. Albence, ICE’s acting director, Trump called “the sanctuary city of New York” out by name in his State of the Union address in February, saying local policies led to the rape and murder of 92-year-old woman in Queens a month earlier.

The president’s address set the tone for what was already in the works: a politicized enforcement campaign that would see an increasing number of New York City community members picked up and sent to surrounding detention centers.

Genia Blaser, a senior staff attorney at the Immigrant Defense Project, began noticing a shift in ICE enforcement patterns in January. For years, Blaser and her colleagues have tracked ICE’s on-the-ground tactics using reports from lawyers and community members to build an interactive map of the agency’s raids and arrest operations.

ICE’s community arrests were occurring in places where the coronavirus was rapidly spreading — and those people are now in detention.

In the final six weeks of 2019, the IDP had received 10 reports of ICE arrest or surveillance operations around New York City; in the first six weeks of 2020 the organization received 60. The presence of guns was turning up in more of the reports, Blaser told The Intercept, as was a curious increase in ICE’s of use mobile fingerprinting technology. “We’re regularly hearing reports of eight to 10 agents making arrests, whereas maybe before you’d hear like four to six,” Blaser said. “Everything is more aggressive.” In a January 24 letter to the New York City Council, co-signed by Immigration Committee Chair Carlos Menchaca, the IDP described “an alarming increase” in ICE’s use of so-called collateral arrests — when the agency takes individuals into custody who were not the intended target of their operation — as well as ICE officers’ continued practice of presenting themselves as New York City police and the ongoing arrests outside local courthouses.

Rosa Santana, the program director of First Friends of New York and New Jersey, a nonprofit that works directly with people in immigration detention, noticed the shift, too. While the jails ICE works with are not at capacity, she said, the composition of the detained population has gone through some important shifts in recent months. The Trump administration’s virtual shutdown of asylum at the border has meant fewer beds filled at the New Jersey detention centers, Santana explained. At the beginning of the year, her organization began noticing what looked like an effort to fill those empty beds.

“New people were coming to the facilities from the community arrests,” Santana said. These were people who were arrested going to court, people who had minor encounters with the NYPD, and, in a new and surprising ICE tactic, people who were arrested dropping their loved ones off at the airport. Rather than being filled with an overflow of people arrested on the border, as was the case last summer, the detention centers became increasingly populated with people from local communities. What’s troubling, Santana acknowledged, is that ICE’s community arrests were occurring in places where it is now clear that the coronavirus was rapidly spreading — and those people are now in detention.

Inside the Varick Street courthouse in Manhattan, where immigration cases in New York City are heard, Sáenz and her colleagues found themselves flooded with new cases. “We knew that there had been a massive rise in home and street and court enforcement in the middle of January,” Sáenz said. “We can tell because we’re there on intake.”

Initial removal hearings in New York immigration court between December 2, 2019, and March 24, 2020. Initial removal hearings for immigrants in ICE custody typically occur about two weeks after an arrest takes place.

Graphic: Soohee Cho/The Intercept

That choice came to light through an internal email the New York Times obtained in early March, revealing that ICE had launched a 24-hour surveillance and enforcement campaign in New York and eight other sanctuary cities with the goal of arresting as many undocumented immigrants as possible. In the words of one official who spoke to the paper, the aim of Operation Palladium was to “flood the streets.” The crackdown came just one month after the Department of Homeland Security confirmed that it would be redirecting what are essentially Border Patrol SWAT teams from the border into cities that had resisted the president’s immigration agenda. Sixty lawmakers signed a joint letter arguing that the move would “not make our streets any safer.”

In New York City, the inherent dangers in street-level immigration enforcement were already apparent.

The morning after Trump’s State of the Union, ICE officers showed up at a home in Gravesend, Brooklyn, looking to arrest Gaspar Avendaño Hernández, an undocumented Mexican construction worker who had previously been deported following an assault conviction. During the operation, ICE officers used a stun gun on Avendaño. An officer also fired his service weapon at Erick Diaz-Cruz, the 26-year-old son of Avendaño’s longtime girlfriend. The bullet passed through Diaz-Cruz’s hand and lodged in his neck. ICE claimed that the officers were “physically attacked,” that the shooting was justified, and that the incident would never have happened if not for New York’s sanctuary policies.

Diaz-Cruz has filed a lawsuit against the immigration enforcement agency. In the wake of the shooting, Reps. Jerrold Nadler, D-NY, and Nydia M. Velázquez, D-NY, sent a letter to Albence, ICE’s acting director, expressing their “serious concern” over the incident. Mayor Bill de Blasio told local news station NY1 that the shooting was further evidence of ICE being “a more and more illegitimate force” and a “highly politicized agency.”

“It’s basically a wing of the Donald Trump campaign at this point,” the mayor said.

Photo: Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images

Ignoring the Coronavirus Threat

As the battle over ICE’s tactics in New York City raged in January and February, White House officials in Washington, D.C., were receiving a steady stream of intelligence laying out the threat that the coronavirus posed. “The system was blinking red,” a U.S. official with access to the classified reporting told the Washington Post.

New York City saw its first confirmed case of the coronavirus on March 1. City health officials braced for a wave of infection with the potential to leave nearly 51,000 people dead. Though the White House was well aware of the crisis headed its way, the administration’s aggressive immigration enforcement efforts in New York marched on.

In the early morning hours of March 9, a team of approximately 10 ICE officers descended upon a two-story home in New Rochelle. Starting from the bottom, the officers checked building residents for their IDs. They then made their way to the second floor, where they spotted the man they were apparently searching for. According Diane Lopez, one of the man’s two attorneys, the officers said they had a warrant but never produced one. The man was arrested as his wife and children looked on.

The following day, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo declared a one-mile containment area around the city. “It is a dramatic action,” the governor said. “But it is the largest cluster in the country, and this is literally a matter of life and death.”

“If I had to speculate the reason that they did any of these arrests, it’s because they knew the person was at home.”

An ICE official said in an email to The Intercept that the man who was arrested had “pending criminal charges with local authorities.” The agency did not say what his alleged immigration violations were. “The individual was screened by medical staff prior to entering the facility for detention, which is common practice for all new arrests,” ICE went on to say. “The detainee is in good health.” When asked if its standard screenings are capable of detecting the coronavirus, ICE said it was adhering to guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Lopez said the operation was inexcusable. “I don’t see how anybody can justify it,” she told The Intercept. Delaney Rohan, a Legal Aid attorney working the immigration side of the man’s case, spoke to his client on Wednesday. The man was being held at the Bergen County detention center, where a detainee recently tested positive for Covid-19. ICE, however, denied that the New Rochelle arrestee was ever at the Bergen facility, writing in an email that he is currently “housed in a facility that to date has not had a positive among the ICE detainee population nor was required to quarantine.”

Rohan, who was perplexed at the discrepancy, told The Intercept that nothing about his client’s case jumped out as significant enough to merit sending a team of officers into a coronavirus hotbed, removing an individual from that infected community, and placing him in a confined immigration detention setting. Coronavirus guidance from the CDC urges law enforcement to only transfer people from one jurisdiction to another, such as New Rochelle to Bergen County, when it is “absolutely necessary.”

“The circumstances surrounding the home raid and the arrest are egregious,” Rohan said. “If I had to speculate the reason that they did any of these arrests, it’s because they knew the person was at home.”

The New Rochelle arrest was one of several examples of ICE operations reported amid the worsening coronavirus crisis that Immigrant Defense Project Deputy Director Mizue Aizeki included in a March 17 letter to New York City council members. On the same day that ICE was making the arrest in New Rochelle, Aizeki wrote, officers were also making arrests and appearances at the New York County Criminal Court and the Queens Criminal Court. The following day, a team of ICE officers were reported at a family shelter in midtown Manhattan. The morning after that, three ICE officers and two Border Patrol agents were filmed knocking on apartment doors in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Aizeki said she couldn’t recall ever hearing of the border enforcement agency operating so deep in the borough. “It’s totally new,” she said.

All the while, the threat of coronavirus in New York City grew deeper and more evident. On March 13, Trump declared a national emergency. The next night, New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was at LaGuardia Airport confronting an ICE officer about reports that the agency was flying immigrant children into the city in the midst of the pandemic. Ocasio-Cortez later joined her New York colleague Velázquez in calling on ICE to “immediately release all immigrants in ICE detention, beginning with all vulnerable populations.”

The doctors detailed the unique dangers people in detention face, writing that “social distancing is an oxymoron.”

The lawmakers were not alone in expressing concern. In a seven-page letter sent to Congress on March 19, two DHS medical experts endorsed the release of people in ICE detention. Describing current circumstances as a “tinderbox,” the letter echoed an opinion piece the experts had published in the Washington Post just days earlier. “We are writing now to formally share our concerns about the imminent risk to the health and safety of immigrant detainees, as well as the public at large, that is a direct consequence of detaining populations in congregate settings,” wrote doctors Scott A. Allen and Josiah D. Rich. The doctors detailed the unique dangers people in detention face, writing that “social distancing is an oxymoron” in those settings.

Less than a year ago, dozens of individuals at the Bergen County Jail were quarantined for weeks during a mumps outbreak. In a scathing report published last summer, the Inspector General of DHS said conditions at the Essex County facility in New Jersey were “egregious” and “endanger detainee health.” In court filings last week, New York City attorneys wrote that there is “a history of denial of vital medical treatment” at the jails that feed into Manhattan’s immigration court.

Sáenz and her colleagues first began receiving distressed calls from clients in the Bergen and Hudson facilities early last week. Because most of the jails have no viable system for lawyers to call in, Sáenz explained, and because visitations to the jails were severely curtailed or cut off entirely, attorneys were forced to wait for people in detention to reach out. “We have massive access to counsel issues on top of worrying for people’s actual safety,” she said.

Immigration hearings involving people in detention have largely continued to lurch forward in Manhattan. Forced to defy the orders of the world’s top epidemiological experts, lawyers are donning masks and protective gear and risking exposure to the coronavirus in order to advocate for their clients. “It’s total chaos from day to day,” Sáenz said last week. The day before we spoke, a judge had told one of her attorneys that she would be gone for the next two weeks. “What’s going to happen to her docket?” Sáenz asked. “We’ve been told nothing. What about everyone on her docket who wants to get out of jail? No information.”

With several attorneys already in self-quarantine, Sáenz has tried to devise measures to mitigate the risks her staff faces, but nothing is perfect. “I feel terrible sending my staff into that situation,” Sáenz said, adding that the only viable solution is for ICE to begin releasing people. “Every other solution puts somebody in danger, including my staff.” Unlike law enforcement agencies in the criminal justice system, Sáenz noted, “ICE has so much more discretion to release, and they’re not using it.”

Jails Packed With People

New York is now the epicenter of the coronavirus in the United States, the jails are still packed with people, and despite the likelihood of widespread death and suffering in the weeks ahead, the Trump administration’s longstanding disdain for New York’s political leaders — most recently Cuomo — appears intact.

On Tuesday, ICE confirmed that a 31-year-old Mexican man held in detention at the Bergen County Jail was the first ICE detainee in the country to test positive for the coronavirus. “ICE’s continued inaction made today’s confirmed Covid-19 case in ICE detention a virtual inevitability and further highlights the urgent need to release all individuals in ICE custody immediately,” the NYIFUP said in a statement. “ICE has refused to heed our demands, and their lack of transparency and outright denial — despite mounting reports of mass quarantines throughout the facilities — is nothing short of criminal.”

Two days later, ICE confirmed that a second detainee had tested positive for the virus, this time at the Essex County Correctional Facility. In a potentially ominous sign of what’s to come, the agency now has a running tally on its website to track similar cases in its facilities.

In recent days, people detained by ICE in New York area jails have found ways to share their stories with the outside world. They have detailed the fear of seeing corrections officers coming and going from their facilities, not knowing if they are returning with the virus; the depression of being separated from their loved ones in a time of crisis; and the reasons that so many of them are now refusing to eat.

Lawyers in New York City continue to work around the clock in a desperate race against time to free their clients and avert a disaster. On Thursday night, they received a glimmer of hope when a federal judge ordered the release of 10 medically vulnerable people from three New York area detention facilities following a petition filed by the Brooklyn Defender Services. On Friday, a second judge ordered the release of four more people following a lawsuit filed by Legal Aid and the Bronx Defenders.

While the wins are significant, tens of thousands of others remain in custody. If ICE doesn’t take action soon, Schlanger, the law professor and former DHS official, said, the consequences could be historic. “This is going to be one of those ‘where were you?’ kinds of things,” she said. A moment when people, years from now, will be forced to answer the question from their grandchildren: “What did you do?”

Ryan Devereaux | Radio Free (2020-03-27T17:20:24+00:00) How ICE Operations in New York Set the Stage for a Coronavirus Nightmare in Local Jails. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/03/27/how-ice-operations-in-new-york-set-the-stage-for-a-coronavirus-nightmare-in-local-jails/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.