Richard Carrillo walked out of the Federal Correctional Institution at Otisville feeling nervous. It was March 24 and he was getting ready to board a shuttle bus in Middletown, New York, to make the 70-mile trip to Port Authority in Manhattan — the first leg of a long journey home. “I didn’t think it was safe at all, to be honest with you,” he said. Carrillo had been following the news. He knew that New York City had become the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic. “I mean, I’m just getting out of BOP and you’re gonna send me to Manhattan to wait at the bus terminal for one, two, three, five hours?”

Carrillo’s travel had been arranged months earlier, before the coronavirus gripped the country. But by March 18, the day the U.S. Bureau of Prisons confirmed its first two cases, FCI Otisville had suspended visitation and gone into “modified lockdown,” reducing access to recreation and dining to one housing unit at a time. The attempts at social distancing were futile. In the medium-security facility where Carrillo was housed, men were double-bunked, with more than 100 people per unit. Just days before his release, he said, men in his unit were subjected to random breathalyzer tests that required blowing into a small funnel attached to a portable machine. “There’s no way you’re going to tell me right now that germs or particles aren’t gonna blow up in your face,” he said.

Carrillo was arrested on federal weapons charges in 2013. Based on his previous convictions, he was sentenced to 8 1/2 years under the Armed Career Criminal Act but won early release after a portion of the law was declared unconstitutional. Back home in Moorhead, Minnesota, he found a job, a house, and gained partial custody of his daughter. He also got involved in his community; in 2019, he helped organize the first Juneteenth celebration in Moorhead, appearing on the local news. But later that summer, Carrillo violated the conditions of his probation by drinking with some guys who also had felonies on their records. After 20 successful months on the outside, he was sent back to prison.

With tests for Covid-19 scarce on the outside, there was little reason for Carrillo to expect to be tested before his release from Otisville. Staff just took his temperature and sent him on his way. At the Port Authority bus terminal, “the whole six-foot distancing was pretty much thrown out the window,” he said. People were coming and going, some approached asking for change. After more than four hours at the station, he boarded a Greyhound bus for a two-day trip with stops in Pittsburgh, Chicago, Milwaukee, and Minneapolis. “We were not distanced on that bus at all. At all.”

Carrillo’s destination was a halfway house in Fargo, North Dakota, just over the river from Moorhead. On his way, he called the facility, which is run by a nonprofit called Centre Inc., and warned a program manager that he had just been in New York City. When he finally arrived late at night on March 26, he again had his temperature taken and was told he would be quarantined. Instead, he was placed in a room with a man who had just come from a different federal prison — and “I was able to mingle and mix with every other person in the building, including staff.”

Even more disturbing to Carrillo, he was told to start looking for work, which meant going out for job interviews. He had little choice but to comply, since it is a condition of his release. On March 31, the same day the BOP announced a 14-day quarantine across its prisons, Carrillo went to an interview at a pawn shop downtown. Later, he called his mother, who was stunned. “She said, ‘I don’t think they’re supposed to be doing that.’” Carrillo said he was briefly isolated after he raised concerns. But it was too little too late. If he was infected in New York, “you just exposed the whole city and this whole halfway house,” Carrillo said.

In an email, BOP spokesperson Sue Allison said that medical screening and quarantine are now requirements for people transferring to the community, but she did not specifically address halfway houses. She did not respond to questions about the BOP conducting breathalyzer tests.

Centre Inc. Executive Director Josh Helmer said the halfway house was following Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. New arrivals are “placed in a sleeping room designated for quarantine in accordance with CDC recommendations, and monitored by on duty staff,” he wrote, adding that “residents are quarantined individually, as long as sufficient rooms exist. If necessary, residents who are quarantined because of travel who pass the screening could be quarantined with a roommate.” As for job interviews, “residents can be approved to participate in an interview telephonically and/or in person with appropriate precautions in place,” he said. But Carrillo, who had another interview at a grocery store on Monday, said the halfway house has not provided masks for such outings.

Today, Carrillo says the rules do seem to have grown slightly stricter since his arrival. He is not showing symptoms of Covid-19. But he and his family have other reasons to worry. His younger brother Shawn is incarcerated at a different federal facility, FCI Atlanta. To date, 16 people at the prison have tested positive for Covid-19, including three staffers. In an email to Carrillo last month, his brother wrote that things were getting bad. They were barely getting enough food or toilet paper and had no access to the commissary in order to buy soap. “He goes, ‘If you don’t hear from me in the next few days, know I love you, know that I care about you, and God bless you. I’ll talk to you as soon as I can.’”

The Federal Correctional Institution, Otisville, in Mount Hope, N.Y.

Photo: Bureau of Prisons via AP

An Uphill Battle

As the coronavirus outbreak has spread inside the nation’s prisons and jails, people inside and outside BOP facilities describe a system mired in chaos. Families are scared and mostly in the dark. “They’re unbelievably stressed out,” said Kevin Ring, president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums. “And they have terrible, terrible stories of what’s happening.”

The anguish and anxiety are not entirely new. Although the threat posed by Covid-19 is certainly unprecedented, it’s also a magnified version of a struggle that is all too common. It is often impossible under ordinary circumstances to get timely or reliable information about loved ones on the inside. Advocating for improved conditions or medical care has always been an uphill battle, let alone for early or compassionate release.

As the crisis has escalated, the BOP has rolled out a series of “action plans” aimed at combating the virus’s spread. Visits have been eliminated and transfers have largely been halted. But many of the precautions have come too late, if they have been implemented at all. On the section of the BOP’s website tracking Covid-19 cases, the numbers are rising every day. At Otisville, 13 cases have been confirmed since Carrillo was released, including five employees. As of April 14, the BOP had confirmed 694 total cases — 446 incarcerated people and 248 staffers. Fourteen incarcerated people have died of Covid-19 to date, according to the bureau.

Four of the fatalities have been at FCI Elkton in Ohio, where a new death was reported on Monday night. This week, the Ohio Justice and Policy Center and the American Civil Liberties Union of Ohio filed a lawsuit on behalf of men incarcerated at Elkton, who described cramped, unhygienic conditions. One man said medical personnel were “taking temperatures using the same thermometer for multiple people and only wiping it off with a sanitary napkin.” The petition seeks the immediate release of individuals vulnerable to the virus, along with those who are close to their release dates.

The lawsuit comes on the heels of a disturbing video recorded on a contraband cellphone and posted on Facebook, which showed a man at Elkton wearing a mask and saying that they were being left to die. Vice News later identified the man; prison officials said he was negative for Covid-19 and denied most of his claims.

On April 6, the day that the Vice story broke, Brenda Cooper’s husband called her from the prison. He asked her if she’d seen the video, then waited while she looked it up. “To me, it’s just terrifying,” she said. “I don’t want to lose my husband.”

Cooper, who is going by a pseudonym to protect her husband’s identity, lives in Manchester, Kentucky, where she works at a manufacturing plant. In the years since her husband went to prison, she has only been able to make the trip to see him once a year. The prison in Lisbon, Ohio, is hundreds of miles away. Between a hotel, gas, and meals, “I don’t have the money to go up there all the time,” she said. “I make $9.50 an hour.”

“This is a sickness that they need to take serious. And they’re not.”

The situation feels all the more senseless given some of the alternatives closer to home. The plant where she works sits in the shadow of FCI Manchester, a medium-security BOP prison. If her husband were there instead of in Ohio, she could make the drive in 15 minutes. “It’s just really hard the way that they place everybody,” she said. “It’s like they try to hurt the family as much as they can.”

When Congress signed the First Step Act in 2018, one of its bright spots was supposed to be a provision that would allow people in federal custody to be moved closer to home. But thus far, the law has not lived up to its promise. The transfers rely on the discretion of the BOP, which makes housing decisions based on numerous factors, from the programming available at a given institution to the need to keep co-defendants separate. Ring, who was instrumental in ensuring the passage of that provision, is disappointed with how it has played out. “I think the exception is still swallowing the rule,” he said.

For Cooper, it would not have made a difference anyway. The provision applied only to people incarcerated more than 500 driving miles from home. Her husband is some 430 miles away.

Cooper makes no excuses for her husband’s past. “He was on drugs and he was wild. He put me through hell the last two years he was home.” But he’s different now, with a good behavioral record, she said. She wishes that the BOP could release more people. “Let them wear an ankle bracelet, you know, home confinement. They’re just so crowded together, there’s no way that [the virus] is not gonna sweep through there. … I stay a nervous wreck about him anyway,” she said. “But to me, this is a sickness that they need to take serious. And they’re not.”

Halfway Home

While Carrillo was on his way to the halfway house in Fargo on March 26, U.S. Attorney General William Barr issued a memo directing the BOP to transfer certain “eligible inmates” from prisons to home confinement. “Many inmates will be safer in BOP facilities where the population is controlled and there is ready access to doctors and medical care,” he maintained. But for others, including older people susceptible to the virus, home confinement would be “more effective.”

That same day, Families Against Mandatory Minimums sent a letter to the Department of Justice. The $2 trillion coronavirus stimulus bill passed in late March allows the BOP to extend the amount of time a person in custody can be placed in home confinement, Ring wrote. Ordinarily, it cannot exceed six months or 10 percent of a person’s sentence, but the CARES Act allows for the relaxation of this rule. Ring urged the BOP to “quickly transfer prisoners who are at high risk for complications from Covid-19 to home confinement.”

The following week, Barr issued a second memo authorizing the expansion of home confinement under the CARES Act. The BOP now says it has released more than 1,000 people to home confinement since March 26, but the figure is misleading at best. For one, transfers are only conducted after a 14-day quarantine at a given BOP facility — and being approved does not mean being immediately quarantined. An untold number are still waiting. What’s more, families have described a chaotic process across the country, with loved ones approved for home confinement placed in the same special housing unit as people isolated due to symptoms. In a text message this week, Cooper also echoed what others with loved ones at Elkton have described: that the majority of men told to quarantine at the prison in preparation for home confinement have actually been returned to their cells.

“I don’t know why they have not cleaned out the halfway houses. … These are the people who are closest to the door.”

Although it is hard to know precisely how many people have actually gotten home, Ring says it is almost certainly a fraction of the total figure cited by the BOP. And despite Barr’s suggestion that those who are older and most vulnerable would be prioritized for home confinement, instead it has been mostly those serving time for low-level offenses who are close to their release dates. When it comes to halfway houses, “I don’t think I know what the policy is even if there is one,” Ring said. At the moment, each facility seems to be making its own rules, with many residents describing crowded conditions. “I don’t know why they have not cleaned out the halfway houses,” Ring added. “To me the halfway houses are worse for social distancing in most cases than the prisons are. And these are the people who are closest to the door.”

Helmer, the Centre Inc. director, said “we have substantially increased our use of home confinement to help mitigate any possible spread of the virus, including those who are most vulnerable.” But Carrillo has been told that home confinement is not an option, even though he is already on an ankle monitor — and even though he has a house minutes away where he could easily self-quarantine. At 42, he is not within the age group at greatest risk, but he does have a history of seizures that could compromise his health. Although Helmer said that no one has tested positive at any of the Centre Inc. facilities, the arbitrary rules and lack of precautions Carrillo describes create a risky environment. After a scare about a possible exposure at the halfway house on Friday night, a neighbor brought him Easter dinner over the weekend, Carrillo said, which he was able to receive in the parking lot. A supply of hand sanitizer dropped off for him was confiscated for containing alcohol.

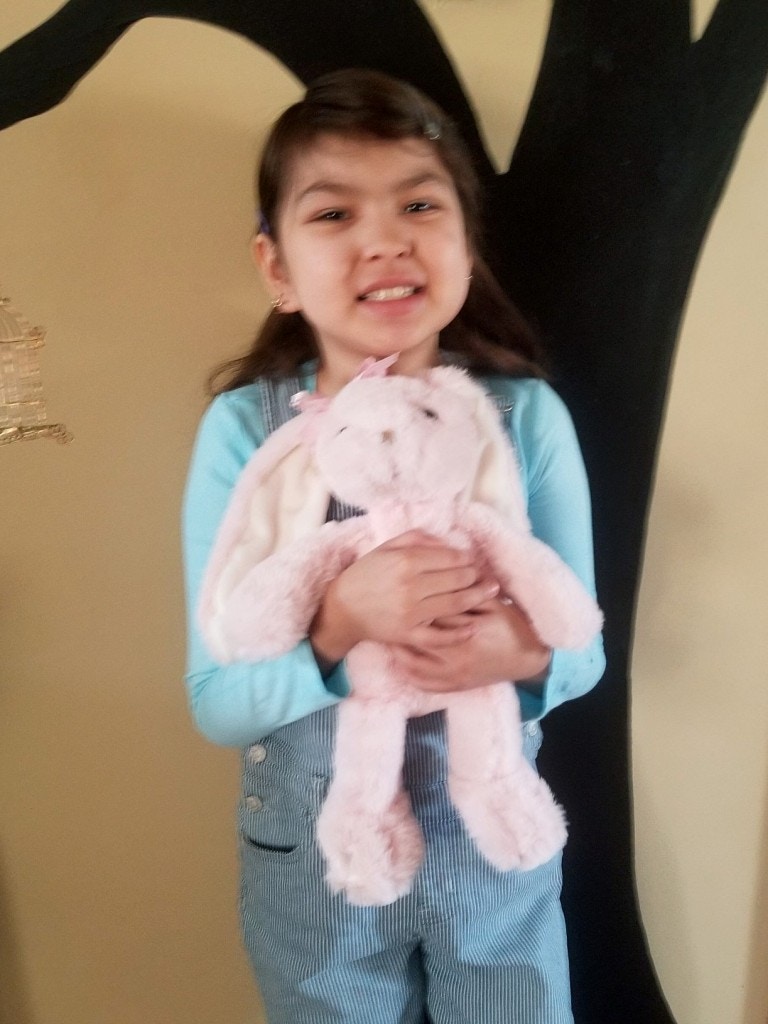

Carrillo’s 8-year-old daughter on Easter this year.

Photo: Courtesy of Denise Johnson

Johnson is especially worried about her youngest son, Shawn. Ironically, it was his good behavior that landed him in his current circumstance. He was in the process of being transferred to a low-security institution when he got stranded at FCI Atlanta. A family friend remembers getting a series of alarming emails last month. In one, Shawn wrote, “This illness will not kill me. I’m healthy plus the Lord has a plan for my life.” But in a subsequent message, he asked for information on the virus, such as the symptoms and death and survival rates.

Carrillo partly blames himself for his brother’s incarceration. “He looked up to me,” he said. “And honestly, you know, my brother wouldn’t be in the situation he’s in if he didn’t look up to me.” Johnson said her son was “more of a follower than he was a leader.” He was just 19 years old when he was arrested on drug conspiracy charges.

In an email Johnson received from Shawn on March 29, he said the virus had gotten inside the prison. “There is a really good chance for it to spread,” he said. “I am trusting God to deliver me, but you never know.” He made some requests in case he died. He wanted to be buried, not cremated. He also wanted to make sure his writing was preserved. It was stored in a clear green trapper keeper, he said. “Maybe you can make use of these things to help others, if the worst should happen to me.” He told his mother he loved her — and “don’t be out running around. Keep yourself safe and trust god.”

Liliana Segura | Radio Free (2020-04-15T16:10:14+00:00) As Virus Spreads in Federal Prisons, People Inside Describe Chaos, While Families Are Left in the Dark. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/04/15/as-virus-spreads-in-federal-prisons-people-inside-describe-chaos-while-families-are-left-in-the-dark/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.