Stephanie Brown was sweating as she pushed her son’s stroller up North Main Street in Covington, Tennessee. She wore gold hoops, flip-flops, and a surgical mask with “I Can’t Breathe” written on it in black marker. Her other two sons walked slightly behind, in the same masks and carrying bottles of Powerade. It was their first time protesting, and Brown’s too. Her reason was simple. “I have three young black boys,” she said, catching her breath.

The marchers had gathered on Sunday, June 14, outside Crumpy’s Hot Wings, a local Memphis chain, next to the Dollar Store on Highway 51. It was around 80 degrees but felt hotter in the plaza parking lot. Some carried umbrellas to shield themselves from the sun. There were participants of all ages, mostly black but some white people too. “Pretty much everybody here is family,” said Nathasha Olden, who had come with her aunt, Anita Wilson. Covington is a small town, she said. “Everybody knows each other.”

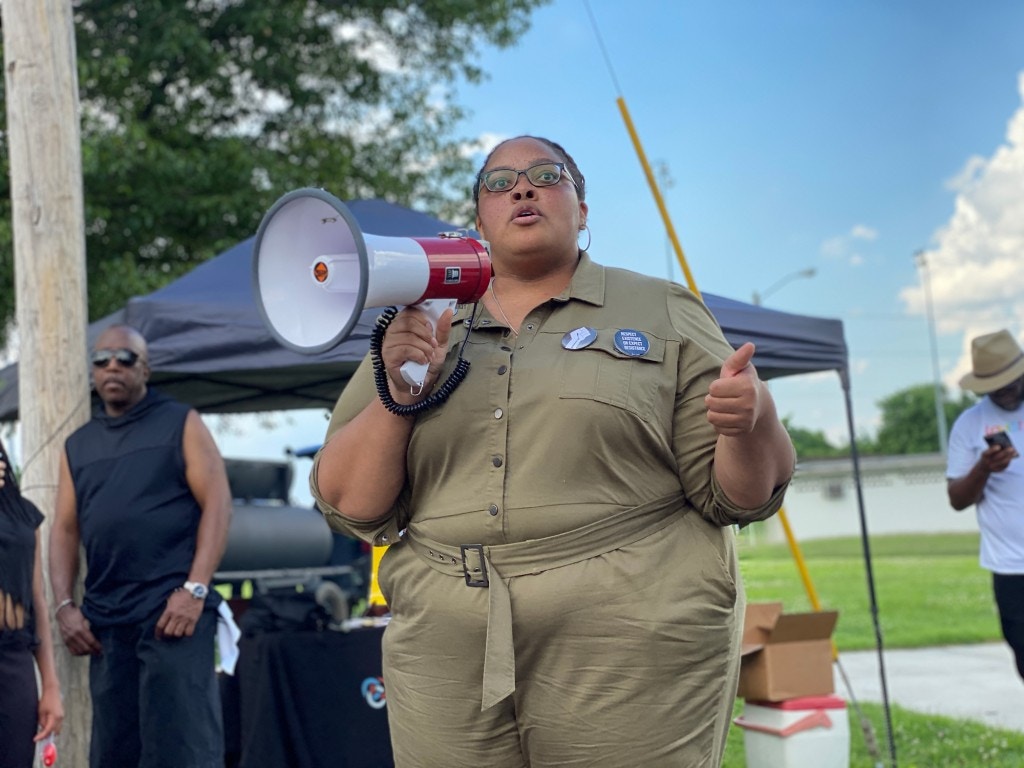

The march had been billed as a “unity walk,” inspired by a recent event in Memphis. One of the organizers, Queisha Harris, had made a point to meet with the Covington police chief right away. She guaranteed that the march would remain peaceful. “We talked about how I would want them to cooperate,” she said. “Protect and serve. And no harassing, because you know, people really don’t want to see the police right now anyway.”

Covington residents Natasha Olden and Anita Wilson at the start of the march on June 14, 2020.

Photo: Liliana Segura

Mike Harris addresses the protesters as a Tennessee State Trooper looks on.

Photo: Liliana Segura

Around 3:25 p.m., Harris’s father Mike addressed the crowd. Black people had fought for fair treatment for years, he said. But George Floyd’s death was a “wake-up call.” He often thinks about what it would be like if one of his own children or nephews was in Floyd’s position. He urged people to seize on this moment to push back against all the barriers standing in their way. “Many people here today have no doubt thought about, somewhere in your lifetime, wanting to run a business. You wanted to be in a position or in office. Now is the time.”

“I’m not sure many more marches and demonstrations we’ll have,” Harris added. “But they’ll go on and on and on until we’ve accomplished our goal.”

Former alderman John Edwards spoke next. He recalled the numerous black men and women killed by police across the country, including Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor, and Botham Jean. But he also invoked a local controversy. Last year, many in the community were angered by the sudden demotion of two veteran police officers who were close to retirement. One of them, Cavat Bass, was the first black police lieutenant and assistant chief in Covington’s history. After almost 40 years with the department, the new chief eliminated Bass’s position, reducing him to patrolman.

Photo: Liliana Segura

“In the city of Covington, when we have a police officer like [Bass], that works his way all the way through the ranks to make it to assistant chief, with a spotless record,” Edwards said. He was known for ensuring that community members were not mistreated and held accountable officers who did — “and they still work for the police department and he doesn’t? Something is wrong.”

Following a prayer, the crowd set out, led by a group carrying a banner reading UNITY, with a raised black fist. They turned right onto Highway 51 and crossed over toward Main Street as law enforcement followed closely along. The police escort did not deter the chants that have echoed at protests across the country: “No justice, no peace! No racist police!” As the march neared the courthouse square, one man shouted to make sure I was recording his message for all to see: “Get your knee off my neck!”

For a town with fewer than 9,000 residents, the march was sizable, roughly 150 people. Outside of Tipton County, however, it was mostly eclipsed by the larger actions taking place in Tennessee’s larger cities. That weekend, multiple events were happening in Nashville, including an occupation of the Capitol grounds. Activists declared an autonomous zone, named it Ida B. Wells Plaza, and distributed free food and water before being pushed out by police. In Memphis, where protests had been sustained for weeks, a man in a white pickup truck had tried to run over protesters who had blocked off a street — only the latest such incident.

While American cities have attracted the most national coverage and controversy since the death of George Floyd — especially crackdowns by police and damage to property — smaller marches have popped up in areas that many would not expect. Many have been remarkable for taking place in rural areas where the vast majority of the population is white. In Tennessee, on the eastern side of the state, a protest in Clinton (population 10,000) attracted 200 people, as did a prayer gathering in Athens (population 13,000). In West Tennessee, dozens of people rallied in Paris (population 10,000).

But in places with a more even percentage of black and white residents, black-led marches are powerful for confronting an entrenched power structure that still disenfranchises half if not more of the local population. Inspired by the national movement for black lives, they have also clearly been fueled by long-standing injustices in organizers’ own backyard. Just 16 miles north of Covington, in Ripley (population 7,879), dozens of residents protested on June 4, calling on a local sheriff to be fired after he was caught on tape using the N-word.

For Donnell Logan, who was born and raised in Covington and helped organize the event, the fact that such a march was happening at all in his hometown was a big deal. He could not recall anything like it. “I think people never had the courage to talk to the white people to get it done,” he said. In Covington, he added, “we go by old traditions. We ain’t too quick to catch on to things.”

Protesters march down historic South Main Street in Covington, Tenn., on June 14, 2020.

Photo: Liliana Segura

Under the Rug

Located some 40 miles northeast of Memphis, Covington is the seat of Tipton County, founded on Chickasaw land that was overtaken by plantations in the 1800s. The old cotton trade remains inscribed in the routes leading in and out of town, from cotton gins to the railroad tracks, to the car dealerships on Highway 51: King Cotton Ford and King Cotton Chrysler.

West Tennessee held the majority of the state’s enslaved population before the Civil War. Among the region’s most notorious traders in human beings was Confederate general and early Ku Klux Klan leader Nathan Bedford Forrest, who ran a slave depot in downtown Memphis — and whose legacy remains the perennial subject of bitter fights in the state legislature. The week before the protest in Covington, an all-white House committee had yet again blocked efforts to remove the bust of Forrest that sits in the Capitol rotunda.

Driving from Nashville, the exit to Covington is also the exit for Nathan Bedford Forrest State Park, as well as the route to Fort Pillow, the site of an infamous massacre of Union soldiers carried out at Forrest’s command. Yet like most parts of the state, Covington has not amended the official narrative of Forrest as a hero. The city’s website boasts that “the great American cavalry general” made his last public speech to Confederate veterans at a reunion in Covington in 1876. That speech is etched in stone outside the Tipton County Museum, not far from the march’s route.

In the center of Covington’s historic downtown, a Confederate statue stands before the old Tipton County Courthouse. Like many such monuments, it was built decades after the Civil War, as states sought to reassert white supremacy in the backlash to Reconstruction. An inscription on the statue’s base honors the soldiers of the Confederacy as having “illustrated the highest type of American manhood,” followed by a line from “The Sword of Robert Lee”: “Nor braver bled for a brighter land, Nor brighter land had a cause as grand.”

As in many parts of the South, white supremacy in West Tennessee was reinforced during Jim Crow by the resentment of rural white residents who struggled economically. Although Shelby County had the highest number of recorded lynchings in the state, Tipton and surrounding counties were home to deadly acts of intimidation well into the 20th century. Albert Gooden, 35, was lynched in Covington in 1937. One town over, in Brownsville, 31-year-old NAACP leader Elbert Williams was forced from his home by a white mob led by the local sheriff in 1940 and found dead three days later. Last week a petition began circulating to remove Brownsville’s own Confederate statue, invoking the name of George Floyd as well as Ahmaud Arbery, who was murdered by white vigilantes in Georgia earlier this year. “I’m signing for Elbert Williams,” one supporter wrote.

Black residents of Tipton County have sometimes had to speak up to remind their neighbors of this history. In 2009, the Covington Leader published a letter to the editor from a woman named Tanya Jones in nearby Atoka, in response to an article recalling the infamous 1897 murder of a white farmer at the hands of a black man who ostensibly confessed. She reminded the newspaper that black people were often accused of crimes that they did not commit in that era — including her own grandmother’s cousin, Harry Ross, who was lynched in Rosemark, just 17 miles south of Covington. Having allegedly “said something inappropriate to a white woman,” she wrote, he was killed by a group of white men who “forced him out of his house, tied him to their car, and dragged him to death.”

“I’m sure there are other African Americans in this county, beside myself, that can tell of a story when a relative was lynched, assaulted, or mistreated in some way by whites many years ago,” Jones wrote. “Would you like to print these stories? Some things are better left untold, aren’t they?”

“A lot of times, these smaller towns are quiet, you know?” Queisha Harris said. “So like they’re gonna keep their stuff under the rug. Like, look, if nobody’s saying nothing, then we must be good.”

Protesters pass the Confederate monument in Covington’s courthouse square.

Photo: Liliana Segura

White Silence Is Violence

As the march made its way toward Covington’s courthouse square, police officers flanked the Confederate monument. Entering South Main Historic District, home to some of the town’s most affluent residents, handwritten signs appeared prominently displayed on a lawn, with messages like “Tolerating Racism IS Racism” and “White Silence is Violence.”

A bit further down, a white woman stood on her lawn and watched the march go by. She was Rachel Witherington, 34, the local city attorney. “I support the march,” she said, adding, “I’m glad to see it happening in big cities but also small towns like Covington.” Witherington also called this moment a “wake-up call” — or at least it should be, she said. For a lot of white people, “this is probably the first time in this community that they’ve actually seen it in their front yards and not on TV. I hope they’re ready to hear the message.”

As the march turned onto Highway 51 — or Jefferson Davis Highway, as it was officially named in 1920 — an older white man in a red pickup truck sat parked along the route, where he had watched the protesters go by. He was blunt in his assessment of the march. “I think it’s a bunch of crap,” he said.

The man did not want to give his name. But he said he owned a lumber business up the road and did not want to see it attacked. He was mistrustful of the protesters across the country, whom he referred to as radical socialists who were opposed to the good things President Donald Trump has tried to do. He did not expect to see a march in Covington, and he’d come out to make sure there wasn’t a “big stink” over the statue downtown. “We didn’t take part in slavery 200 years ago, all the people that’s living now,” he said.

By 5 p.m. the march was nearing Frazier Park, right around the corner from where it began. Marchers arrived tired but cheerful. There was water and Gatorade, hot dogs and hamburgers, all donated from local businesses. Participants signed the banner while volunteers helped register people to vote.

Shelby County Commissioner Tami Sawyer said a few words. On the Facebook page of the Covington Leader, which was streaming the march, a few white commenters had reacted negatively upon learning that she would be appearing at the march. One said she was coming to spread “her poison” to Covington. Another agreed Sawyer was very divisive.

Photo: Liliana Segura

Sawyer has shaken the white establishment in Shelby County since she was elected in a landslide in 2018. Since then — and following an unsuccessful run for mayor of Memphis — she has been targeted relentlessly by those who see her as a threat. “They are going heavy on her, unfortunately,” a marcher from Memphis told me that day. “She’s just voicing everything that nobody else would. But they just hate to see the change.” To her supporters, Sawyer represents the leadership that’s long overdue in a majority-black city. But she also represents something else.

Sawyer was born in Illinois and moved to Memphis when she was 12. In the summer, she would go to Mason, where her mother’s side of the family was from, and spent time in Covington, where she made lifelong friends. Though she wasn’t really aware of it as a kid eating hot dogs and popsicles on the porch alongside them, “there was a big class difference between me and a lot of my friends out there,” she said. She was no stranger to racism, but “my parents had upper middle class, professional jobs and I went to private school. So to white rural people, it’s like, ‘How dare she talk about oppression?’”

Sawyer was not naive about the way she might be received in Covington. She made a name for herself by leading the charge to take down Memphis’s statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest, which was ultimately removed in 2017. But Sawyer did not come to Covington to advocate for the removal of its Confederate statue. She came to show solidarity with Harris, whom she’s known since she was a kid. Still, she could see why some would be quick to make that assumption. “I think that there’s a fear that the world is is changing more rapidly than they can protect what they consider to be their ancestry,” she said.

To Sawyer, there are other battles to fight. Systemic racism still shapes the landscape in West Tennessee. Since her summers spent in Mason, she has seen firsthand how local jurisdictions have generated economic growth by criminalizing rural black residents has through traffic fines and other infractions. “A year or two ago my uncle had spent a weekend in jail,” Sawyer said. “And when they pulled him over, it was because his car was too nice.” A handyman who works for her parents and who lives off Highway 51 was accused of petty theft and put on probation, then repeatedly picked up by police for being outside an acceptable radius of his house.

As participants headed home after the march, Paul Whitley sat on his porch facing the park. A longtime resident of Covington, he runs a barbershop out of his home. He supports the police, he said. But he believed the protest was a good thing. “We have never been measured up to the point where they treated us equal,” he said. “Never. Not in my lifetime. And I’m 77 years old.”

I asked if he would like to see the Confederate monument come down and he said he would. “Coming in from the South, that’s the first thing I see,” he said, adding that he never understood who, exactly, it was supposed to be. He had been glad to see the removal of the Forrest statue in Memphis. “I never thought that was going to happen.”

Liliana Segura | Radio Free (2020-06-21T12:30:29+00:00) The Movement for Black Lives Confronts the Confederate Legacy in Rural Tennessee. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/06/21/the-movement-for-black-lives-confronts-the-confederate-legacy-in-rural-tennessee/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.