It was getting close to midnight at the Ford dealership on Route 41 in Terre Haute, Indiana, and there was no word yet on the execution. Half a dozen people sat hunched over their cellphones next to a hulking gray pickup truck, awash in the fluorescent lights flooding the lot. It was Monday night, July 13, and Daniel Lewis Lee had been scheduled to die at 4 p.m.

It would be the first federal execution in 17 years. The last time the U.S. government restarted executions after a long pause — killing Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh in a newly constructed death chamber in 2001 — throngs of protesters and national press overwhelmed the city of 60,000. But this was a significantly smaller event. Some 20 protesters had gathered at the intersection in front of the dealership earlier that day. The street that cuts across Route 41, Springhill Drive, leads straight to the entrance of USP Terre Haute, a sprawling supermax prison across from a Dollar General. The demonstration included a contingent of Catholic nuns, Sisters of Providence, from the nearby Saint Mary-of-the-Woods congregation. They held signs, prompting honks, waves, and the occasional expletive from passing cars. “What about the victims?” one woman yelled.

But nearly eight hours later, the intersection was quiet. Most of the protesters had gone home. Around 11 p.m., the son of the owner stopped by the lot; he’d gotten a call about vandals, which proved unfounded. “The dealership people have been really cool,” said Abe Bonowitz of Death Penalty Action as the man drove off. “The nuns buy their cars here,” he added.

In a cloth face mask that read “Abolish the Death Penalty,” Bonowitz refreshed the docket on the website of the U.S. Supreme Court. Following a flurry of litigation, U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan had ordered a temporary stay earlier in the day based on evidence that the government’s execution protocol could cause a tortuous death in violation of the Eighth Amendment. “Eyewitness accounts of executions using pentobarbital describe inmates repeatedly gasping for breath or showing other signs of respiratory distress,” she wrote. The temporary injunction was intended to give the courts a chance to review this evidence, but the Department of Justice had appealed the ruling. With prison officials set to kill Lee as soon as they got a green light, there was nothing to do now but wait.

Adam Pinsker, a reporter for the Bloomington-based public broadcasting station WTIU, sat with the activists in the parking lot. In a suit, tie, and blue surgical mask, he was supposed to be witnessing the execution — one of eight journalists chosen for the task. After reporting to a makeshift media room at the FCC Terre Haute Training Center around mid-afternoon, he’d been driven in a white van to the penitentiary grounds, where he went through security and waited to be taken to the death house. Around 6 p.m., prison staff briefly let the reporters out to get something to eat at a nearby shopping mall. By 10 p.m., they were told they could leave again. Officials would notify them when it was time to come back.

Like the protesters, Pinsker was anxious for updates. Lee’s execution was the first of three scheduled to take place that week — and Pinsker was supposed to witness all of them. From the parking lot, he called a federal public defender to ask a question on everyone’s mind. In most states, a death warrant expires at midnight on the day of a scheduled execution. After that, a new date must be set. The lawyer told Pinsker that the same should be true here. The closer it got to 12 a.m., the less likely Lee would die that night.

Around 11:40 p.m., news finally reached the parking lot: The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit had ruled against the Trump administration, leaving the preliminary injunction in place. The court set an expedited briefing schedule to resolve questions over the execution protocol toward the end of the month — it appeared that all three executions would remain on hold. By midnight, Bonowitz had posted a celebratory video on Facebook and started driving back home.

But at 2 a.m., an unexpected ruling came from the Supreme Court. In a 5-4 decision, the justices vacated the stay. “Please make your way back to the Media Center,” a Bureau of Prisons staffer texted a reporter with the Indianapolis Star, who was at a motel near the prison. “We will be resuming the execution at approximately 4 a.m.”

As the sun came up over the prison, lawyers on both sides were still fighting over Lee’s life. In a small, cramped room, the media witnesses sat for hours in plastic chairs facing two windows covered with shades. “We could hear birds chirping outside and occasionally muffled bits of conversation from other rooms in the building built specifically to carry out executions,” the Star reporter wrote. At 7:46 a.m., the shades finally opened, revealing Lee on the gurney, lying under a blue sheet.

I was on my way to the training center when Lee was pronounced dead at 8:07 a.m. on Tuesday morning. In the parking lot, a local journalist told me what had happened. The hours inside the prison had been long and disorienting, with very little information about what was going on, she said. But the wait was the longest for Lee. “He was strapped to the gurney for like four hours.”

Politics and the Pandemic

From the moment Donald Trump was elected in 2016, the question regarding federal executions was not whether they would return, but when. “We’ve been prepared for this since the beginning of the administration,” one veteran death penalty lawyer told me last summer, after Attorney General William Barr announced that the government would kill five men between December 2019 and January 2020.

Capital defense attorneys were able to beat back the plans for a while. Last November, Chutkan, the D.C. federal judge, blocked the first round of executions, ruling that they would violate the Federal Death Penalty Act, which says that federal executions must be carried out “in the manner prescribed by the law of the state in which the sentence is imposed.” The execution protocol adopted by the Trump DOJ — a one-drug method using pentobarbital — did not exist when the law was passed. In December, the Supreme Court sent the case back to the appeals court, while signaling that it was merely a temporary delay. “I see no reason why the Court of Appeals should not be able to decide this case, one way or the other, within the next 60 days,” Justice Samuel Alito wrote in a statement joined by Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh.

Then came the coronavirus. For most people, the looming return of federal executions was far from a central concern; by the time the appellate court vacated Chutkan’s preliminary injunction on April 7, the pandemic had killed more than 12,000 Americans. But if there were good reasons not to revive executions amid the pandemic, the Trump administration did not seem to care. On June 15, Barr announced new execution dates for four men: Daniel Lewis Lee, Wesley Ira Purkey, Dustin Lee Honken, and Keith Dwayne Nelson. The first three would take place in the same week, beginning July 13.

“If you are interested in the orderly administration of the law, you don’t set three executions for five days after not having done it for 17 years.”

There was never much doubt that Trump’s executions were driven by politics, part of his law-and-order posture entering an election year. The original dates had been announced at the height of the Russia investigation, prompting accusations that the president was seeking to distract Americans from his own malfeasance. Of course, capital punishment has always been weaponized by politicians of both parties. Bill Clinton, who vastly expanded the federal crimes punishable by death when he signed the Federal Death Penalty Act, famously witnessed the execution of Ricky Ray Rector in Arkansas as part of his 1992 reelection campaign.

Yet as Trump’s killing spree unfolded, it was chilling for its ruthlessness as much as its timing. “If you’re interested in carrying out the law, you don’t rush executions while a court is still determining whether your process is legal,” said Robert Dunham of the Death Penalty Information Center. “If you are interested in the orderly administration of the law, you don’t set three executions for five days after not having done it for 17 years.” Although the news out of Terre Haute would soon be eclipsed by images of camouflaged Customs and Border Protection officers descending on Portland, Oregon, the executions were yet another show of state violence staged to bolster the president’s image.

Daniel Lewis Lee waits for his arraignment hearing for murder in the Pope County Detention Center in Russellville, Ark., on October 31, 1997.

Photo: Dan Pierce/The Courier/AP

With a fourth execution already scheduled for late August, the DOJ last week announced three additional execution dates. More are rumored to be on the way. The next man set to die is Lezmond Mitchell, the only Native American on federal death row. As in Lee’s case, the family members of Mitchell’s victims have long opposed his execution, as does the Navajo Nation, where his crime took place. And as in Lee’s case, in which federal prosecutors were overruled by Washington when they sought to take the death penalty off the table, the U.S. attorney in Mitchell’s case declined to seek death only to be overruled by then-Attorney General John Ashcroft.

The insistence on capital prosecutions in jurisdictions without the death penalty generated controversy at the time — a precursor to the federal government’s intrusion on states in the name of justice. But Trump’s push to execute as many people as possible amid a global pandemic is unprecedented. Attorneys for the men executed last month have decried the government’s conduct as lawless and cruel. It is bad enough that a ban on visitation forced sensitive legal discussions to take place over the phone rather than in person. In Lee’s case, attorneys working remotely were kept in the dark as the DOJ immediately issued a new execution notice after the original one expired at midnight.

Lee’s lawyer, Ruth Friedman, had planned to be in Terre Haute when he was given his original execution date last year. But the pandemic kept her at home. There was not enough information about the BOP’s planned precautions — one colleague had been told that they would not be allowed to bring their own N95 masks. The BOP did not respond to my questions about its Covid-19 protocol.

The executions were another show of state violence staged to bolster the president’s image.

“We were on the phone with Danny when he was taken out of his cell” in the early morning hours of July 14, Friedman said of Lee. She did not know his execution was imminent. It was only later that she learned he was lying on the gurney while his lawyers scrambled to stop prison officials from executing him before an order lifting a separate stay had been finalized. They were not even informed before the execution began. “I learned that he was executed from a tweet,” Friedman said.

But perhaps the most callous disregard was toward the very people the Trump administration claimed to be championing: the families of the victims. When Barr first announced that federal executions would resume, he said that “we owe it to the victims and their families.” But in Lee’s case, not only did numerous relatives of the victims oppose his execution from the start, they filed a lawsuit arguing that traveling to witness the execution posed a risk to their lives. Barr “paraded our pain and tragedy around by saying he was doing this for the ‘families of the victims,’” said Monica Veillette following Lee’s execution. Her 81-year-old grandmother, Earlene Peterson, a Trump supporter, said she felt betrayed.

Even for those families who support the executions, forcing them to come to Terre Haute amid a deadly pandemic belies claims that the federal government has their best interests at heart. With the Trump administration’s use of force under scrutiny during Barr’s appearance before Congress last week, it would have been a good opportunity to ask why the government is pushing so hard to carry out killings that could put more innocent lives at risk. As the Trump administration keeps setting new dates while virus cases in Indiana continue to rise, the question remains: Who are these executions for?

Nobody Knows What’s Coming

I arrived in Terre Haute on Saturday, two days before Lee was set to die. Apart from the intense summer heat, the city did not feel all that different from my last visit in December. The governor had not yet implemented a mask mandate, and gatherings as large as 250 people were allowed. Around Route 41, gyms were full, restaurants advertised dine-in service, and a scaled-back version of the Vigo County Fair was underway. Up the street from the penitentiary, a sign in front of Honey Creek Plaza read, “WE HAVE ALL REOPENED.”

Coronavirus cases were rising across Indiana in mid-July. The week after the executions, Vigo County recorded its highest single-week increase to date, which the local health department attributed to sleepovers, pool parties, and other gatherings. The 11 deaths to date include a 41-year-old firefighter and a man in his 50s incarcerated on a probation violation at the federal penitentiary.

With countless BOP personnel, U.S. Marshals, reporters, lawyers, and witnesses set to travel to Terre Haute from around the country for the executions, the risks were plain to see. That weekend, the local Tribune-Star published an editorial opposing the planned executions. “Most reasonable people, whether for or against capital punishment, would agree that postponing these executions until after the pandemic has ended makes sense. … The health of the families and workers involved, as well as the Terre Haute community, matters.” The Vigo County Health Department did not answer my emails inquiring about the potential impact of the federal executions.

On Sunday, I got a phone call from a man on federal death row. Billie Allen, 43, was convicted of a St. Louis bank robbery and murder in 1998, which he swears he didn’t commit. He lived through the last round of federal executions, beginning with McVeigh in 2001 and culminating with Louis Jones, a Gulf War veteran executed on the eve of the Iraq War in 2003. In an email on July 9, Allen described what it was like when someone was taken to the death watch range. “They show up at the cell door, without notice, and no warning,” he wrote. “They tell you to cuff up, and when you ask where you are going, you are met with no answer. But their no response says everything. You are going to see the Warden so that he can read you your death Warrant. That is what happened when they came to get my neighbor, and I haven’t seen him since.”

Photo: Scott Langley

The neighbor was Wesley Purkey, the second man scheduled to die, on July 15. Allen was not close to him. But he echoed what the Trump administration itself has emphasized: that all the men being executed were convicted of murdering children. The point, Allen said, was to advance a narrative about everyone on death row. “Like we’re all child-killers.”

As our phone time ran out, Allen said the whole prison would soon go on lockdown. “Nobody knows what’s coming next,” he said. But “if this goes through, we believe it’s gonna be a slaughterhouse. They’re just gonna try to clear this place out.”

After I hung up, news broke that a prison staffer involved in preparations for the executions had tested positive for Covid-19. In a legal filing, the BOP admitted that the staffer had not always worn a mask during planning meetings but maintained that no one directly involved in carrying out the executions had been exposed. The killings would move forward as planned.

News broke that a prison staffer involved in preparations for the executions had tested positive for Covid-19.

Even before the pandemic raised serious questions about the executions, seeking basic information from the federal government was an exercise in futility. When I first inquired about the selection of media witnesses in September 2019, I was assured that information would be “forthcoming.” When I followed up in November, I was told “we are working on the plans for this and will be back with you as soon as possible.” With the execution dates a week away and no word from the BOP, I wrote back in December and was told that media witnesses had already been selected — “we are not able to accommodate additional media on institution property.”

This time around, I filled out a short online form to be a media witness. In an email a few weeks later, the BOP said it could not accommodate my request but would allow me to report to the FCC Training Center just north of the prison to cover the executions. Temperature checks would be required, and face masks would be issued, to be worn at all times. “Additionally, to the extent practical, social distancing of 6 feet should be exercised.” When I asked if we would be indoors or outdoors, I was told “you will be outside.”

There was no outdoor media area when I arrived at the training center. The small white building was marked by a sign commemorating the penitentiary’s 75th anniversary, with pink and red petunias planted at the doorway. After a woman in a face shield took my temperature, BOP spokesperson Jenna Epplin introduced herself to the handful of nonwitnessing press. “It is critical that we ensure the order and integrity of the process,” she said, then paused. “We’re not recording right now at all, are we?”

Epplin laid out where we were allowed to go. A pair of fenced enclosures had been reserved for the demonstrators, she said, and there were a couple of other outdoor areas designated for press. “All other areas are not authorized.” Confusingly, this included the press room set up in a ballroom a few feet away. Only witnessing reporters had access to the space. When I asked where we would get updates on the executions, Epplin said that the BOP would not be giving updates. When I asked how media witnesses had been chosen, I was told to email the question to the BOP.

If the aim was to dissuade all but a handful of reporters from attending by sending them to stand in a field with no access to information, the guidelines for protesters were designed to do the same. With all three executions originally scheduled for 8 a.m., the BOP initially instructed demonstrators on either side to report to one of two local parks between 4 and 5:30 a.m., after which buses would transport them to a field outside the prison. No phones or electronics would be allowed. After the executions were moved to 4 in the afternoon, demonstrators were told to report to the parks beginning at noon. Nobody came.

“He Took My Daughter’s Last Breath”

On Wednesday morning, an email arrived from the BOP with the subject, “Time Change — TODAY Scheduled Federal Execution.” Wesley Purkey would now be killed at 7 p.m., it said. “Please check your email periodically for any additional updates or changes.”

Of all the executions, Purkey’s was the one that seemed most likely to be blocked. That morning, Chutkan had granted a preliminary injunction based on substantial evidence that the 68-year-old had dementia, Alzheimer’s, and schizophrenia, which would render him incompetent for execution. That same day, attorneys filed an emergency motion opposing the DOJ’s attempts to lift the stay after discovering that the federal government had additional evidence of Purkey’s brain abnormalities but had not disclosed it to his legal team.

There were other, more familiar problems with Purkey’s case. Although there was no question of his guilt for the kidnapping, rape, and murder of a 16-year-old girl named Jennifer Long, Purkey’s childhood had been marked by extreme trauma, which is common among people sent to death row. One forensic psychiatrist reported that Purkey had disclosed that his mother molested him when he was a child — “and it did not end until he was 22 years old.” At trial, prosecutors successfully dismissed these claims as a “fairytale,” even though a number of family members could have corroborated the allegations. A longtime friend named Peggy Noe also told attorneys later on that Purkey had divulged the abuse in a tearful conversation they had as teenagers.

Photo: Scott Langley

Noe could have been a powerful witness for the defense at his trial. But she was never called. Purkey’s trial lawyer was a Kansas City defense attorney named Frederick Duchardt. A lengthy 2016 profile in the Guardian revealed Duchardt’s apparent hostility toward mitigation, the crucial and painstaking process of investigating a client’s history for any evidence that might be used to spare their life. In Purkey’s case, rather than hire a mitigation specialist, Duchardt took it upon himself to interview witnesses alongside an investigator who was a personal friend. In one affidavit, Purkey’s daughter described how the two had shown up unannounced to interview her on her wedding day.

Duchardt has defended his conduct in Purkey’s case. In an email, he wrote that the Guardian article “totally misrepresented my perspectives about the work” while relying on “accusations in post-conviction petitions” to which he has provided extensive answers. Indeed, Duchardt submitted a 117-page affidavit to Purkey’s federal habeas attorneys, aggressively defending his conduct at trial. The move was not only unheard of among capital defense lawyers, who rely on ineffective assistance of counsel claims, but it undermined efforts to save his former client’s life.

“This sanitized murder really does not serve no purpose whatsoever.”

Noe died in 2014, but her daughter, Evette, remained in touch with Purkey. In a phone call last year, she said he was like a member of the family; he used to take care of her when she was little, even though he was always in and out of trouble. “I just wrote to him on and off all my life. He’s always encouraged me with everything I ever went through.” Evette Noe remembered her mother discussing the abuse Purkey had endured as a child. It did not excuse his horrific crimes — before being convicted for murdering Long, he’d confessed to murdering an 80-year-old woman. But the trauma and years of subsequent drug use had set him on a violent path.

In recent years, Noe sent Purkey books and Bibles, and he told her that he had become a Buddhist. As his execution date neared, the American Civil Liberties Union sued the Trump administration on behalf of Purkey’s spiritual adviser, a Buddhist priest who had been ministering to Purkey for 11 years. The priest had lung problems; he sought a stay due to the risks posed by the coronavirus. But the lawsuit was rejected.

Despite the time change, Purkey’s execution went almost exactly like Lee’s. At 2:45 a.m., the Supreme Court again voted 5-4 to vacate the preliminary injunction, which had been upheld by the appellate court. His attorneys, working remotely, saw media witnesses tweeting that the execution would proceed, then rushed to file court challenges to keep officials from killing their client. In Terre Haute, four reporters who had watched Lee die just 24 hours earlier spent the whole night on the prison grounds alongside other media witnesses. This time, they were not allowed to leave for dinner. Prison staff provided peanuts and Lunchables.

Purkey was declared dead at 8:19 a.m. In his last statement, he apologized to Long’s family. “I deeply regret the pain and suffering I’ve caused Jennifer’s family,” he said, but added, “This sanitized murder really does not serve no purpose whatsoever.”

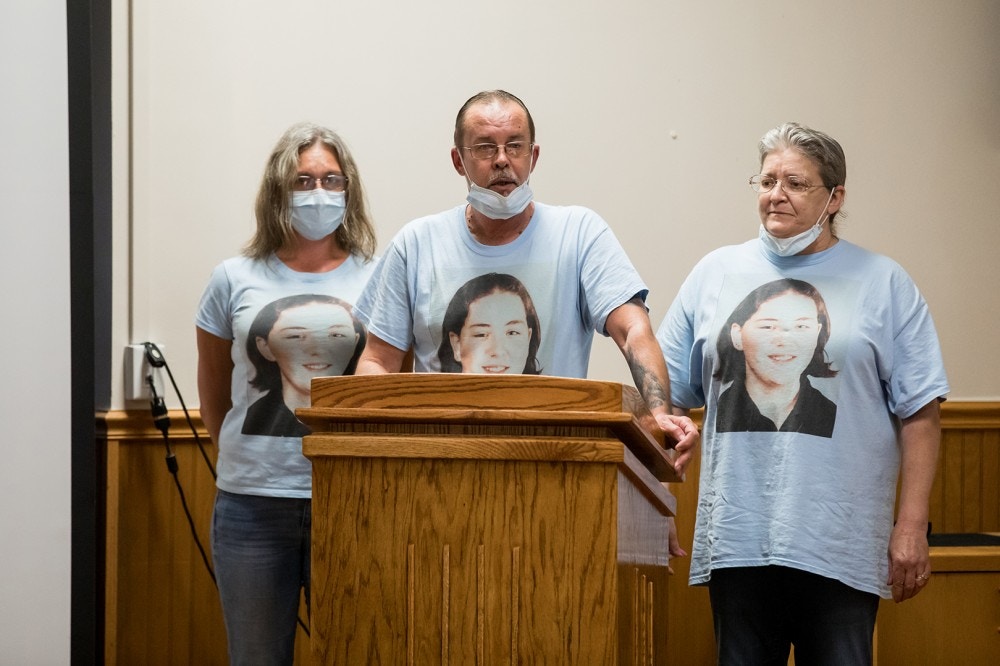

Shortly after the execution, three members of Long’s family entered the media center. They wore blue T-shirts with her picture on them. They were angry over Purkey’s final appeals, and the long wait for his execution. One relative said they had sat in a van for four hours while waiting on news from the courts.

“There’s monsters out there that need to be gotten rid of,” Long’s father said. “They need to be put down like the dogs they are. There’s no excuse for it.” He did not accept Purkey’s apology. To him, the statement was perfectly lucid, proof that Purkey’s supposed mental health issues were merely a delaying tactic. “He needed to take his last breath because he took my daughter’s last breath. There is no closure. There never will be because I won’t get my daughter back.”

“That Execution Did Nothing for Me”

Later that day, I met up with a Terre Haute resident named Lorie Kindred in Voorhees Park, the designated gathering spot for pro-death penalty demonstrators. Sitting on a park bench and wearing a blue face mask, she shared her own experience with the death penalty, which she does not talk about very often.

Kindred’s younger sister, Delores Wells, was abducted, tortured, and brutally murdered in 1987. It was one of Vigo County’s most famous crimes; the perpetrator, Bill Benefiel, was sentenced to death and executed in 2005 — one of 20 people executed in the state of Indiana since 1981.

“That execution did nothing for me,” Kindred said. “I didn’t feel one way or another about it.” But she became emotional talking about her mother, Marge Hagan, who died in 2016. The last time anti-death penalty activists descended on Terre Haute, Hagan and her husband had repeatedly faced off against the abolitionists, becoming the face of the pro-death penalty side. As Kindred recalled it, her mother was not a fervent believer in capital punishment, but she wanted to ensure that Benefiel and men like him could never hurt another person again. By the time his execution was carried out, Kindred said, “she had a lot of hate in her heart. And it changed her. But you know, the end result was she felt justice had been served. And that’s really all that mattered.”

Kindred still has survivor’s guilt over the death of her sister. “The last time I saw her was on my 25th birthday,” she said. “We were at my mom’s house and having cake and then she disappeared. She was abducted the next day.” When the trial came around, Kindred was struggling with drugs and alcohol; by the time Benefiel was set to be executed, she was sitting in a county jail, preparing to go to prison for the first time. But her public defender was able to get her a furlough to go with her family to Michigan City, where the execution would take place.

Delores Wells during the summer of 1985.

Photo: Courtesy of Lorraine Kindred

It was years later, while serving another prison sentence, that Kindred realized she needed to work through her trauma. In a counseling program, she confronted her feelings about her sister’s murderer. “I had to humanize him. I had to forgive him,” she said. “I never told my mom I did that. I felt like I’d be betraying her.”

Kindred doesn’t take sides on the death penalty now, although it bothers her that her sister’s grisly death is brought up every time capital punishment is back in the public eye. “I’m a proponent of second chances. And third chances,” she said. But “it’s not up to me to decide what anybody’s fate is. I wouldn’t want that task. I wouldn’t want to sit on a jury that had to decide that.”

Today, Kindred works as an addiction counselor in a prison 45 minutes outside Terre Haute. “I have my clients write an autobiography so that I can get to know them a little bit,” she said. “And I read three today that would just break your heart.” The cycles of violence, trauma, and addiction are so clear to her now. If she could redirect the resources poured into the executions that week, she said, she would spend them on mental health.

“This county is really not any different probably than any other county,” she said. “The opiate crisis is here, people are dying. We need to help the people that are still trying to fight to live.”

The Sharks Keep Coming

On my last day in Terre Haute, the protesters returned to the Ford dealership around 3 p.m., an hour before Dustin Honken was set to die. There was a sense of weariness, if not defeat. They were already planning to return in August for the next federal execution, including veteran abolitionist and Indiana native Bill Pelke, who had traveled from Alaska. “Sometimes all you can do is stand up and say it’s wrong,” he said.

Of the three men executed that week, Honken had the most blood on his hands. He was serving a 27-year prison sentence when he was tried and convicted for the death of five people, including two children, as part of a drug ring in Iowa in 2004. Although Iowa has not had the death penalty since 1965, then-Attorney General John Ashcroft brought federal charges, winning the first death sentence in the state in 40 years. Honken’s girlfriend, Angela Johnson, was also sentenced to death, but her sentence was later commuted to life without parole.

With few remaining legal avenues to pursue, Honken was executed on schedule. After he was declared dead at 4:36 p.m., the families of his victims released statements via the BOP. “Finally, justice is being done,” wrote the relatives of Lori, Kandace, and Amber Duncan. “It will bring a sense of closure but we will continue to live with their loss.”

Before leaving town, I spoke to Sister Betty Donoghue, who visited Honken on death row for 10 years. Donoghue never planned to befriend someone on death row. It was only after one of her fellow Sisters of Providence, Rita Clare Gerardot, had been a long-time visitor to another condemned man that Honken asked if there might be a sister who could visit him too. “And I was the lucky one,” Donoghue chuckled.

“One time he said to me, ‘You know, every man up here is a broken person.’”

Despite Honken’s horrific crime, Donoghue described him as a blessing in her life. In the years she got to know him, Donoghue saw Honken develop empathy for the other men on death row. The realization that so many had experienced trauma of some kind early in life was a profound discovery for him, she said. “One time he said to me, ‘You know, every man up here is a broken person.’”

Donoghue got to know Honken’s mother, as well as his daughter, Marvea Johnson, who was just a child when both her parents were sentenced to die. As Johnson grew older, she continued to visit her father on death row while spending time with the sisters at the Saint-Mary-of-the-Woods campus, a lush and peaceful place that used to host death-row families on the grounds. It was there that Johnson spent her father’s last moments.

When they said their goodbyes on the phone earlier that week, Honken told Donoghue how much it bothered him that Daniel Lewis Lee had been strapped to the gurney for hours before his death. “Danny and Dustin were very, very good friends,” Donoghue said. Like Honken’s loved ones, Lee’s family also visited him in Terre Haute over the years and got to know the Sisters of Providence. Before he died, Lee sent a letter to Gerardot, which she received after his execution. “I wanted to express my gratitude to you,” he wrote. “I still think of you ladies as beacons of light. In the coming days I have several visits with my family. I hope they have a chance to see you again.”

Photo: Scott Langley

After returning home from Terre Haute, I got an email from Allen, Purkey’s neighbor on death row. The execution lockdown had been lifted. But the events were seared in his mind. “We all sat in our cells, many watching every news station that would report any and everything about the executions,” he wrote about the first night. The local news stations had the most detail, he said. “They made sure that with every segment, they highlighted the cases, and especially the crime’s details. But that’s to be expected when they are trying to tell people that it’s OK to kill another human being. They need people to feel that the human being isn’t a human being anymore.”

As the night wore on inside the prison, no one seemed to know what was happening, Allen wrote. “Even the officers could be overheard asking what was going on. It felt like a Black Ops operation, where they wanted to keep everything quiet. … I didn’t stay up all through the night to see what happened, but when I woke up the next morning, that’s when I learned that they had followed through with their first killing. We too learned that they kept Danny strapped to the gurney from the time they gave him his date until several hours until they executed him! Yes, he had to stay strapped down that entire time with a needle in his arm, people in the room waiting, looking at a clock, waiting to see if he was going to be killed! It then created a wave of conversations that made people really wonder who would be next and if they would have to go through the same thing. Because as they say. Once there’s blood in the water, the sharks keep coming.”

Liliana Segura | Radio Free (2020-08-02T13:30:39+00:00) Disregarding the Virus and Victims’ Families, Trump Rushes to Execute as Many People as Possible. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/08/02/disregarding-the-virus-and-victims-families-trump-rushes-to-execute-as-many-people-as-possible/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.