Janine Jackson interviewed constitutional law attorney Kia Rahnama for the September 11, 2020, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript.

Politico (8/17/20)

Janine Jackson: The cop yanking down a protester’s mask to pepper spray them in the face most likely isn’t thinking, “Well, if it comes to it, I’m pretty sure John Roberts has my back.” But Supreme Court rulings do form part of the backdrop, the climate, in which police officers feel comfortable doing such things. “The system” has their back, and the Supreme Court is part of that system. Surprising, maybe, as many people protesting may believe that ultimately the legal system supports them, in the form of the First Amendment. As our next guest explores in a recent article, it’s a bit more complicated than that.

Kia Rahnama is a constitutional law attorney as well as a writer. His article, “How the Supreme Court Dropped the Ball on the Right to Protest,” appeared recently in Politico. He joins us now by phone. Welcome to CounterSpin, Kia Rahnama.

Kia Rahnama: Thanks for having me, Janine.

JJ: Well, let’s leap right in. We tend to toss around the term “First Amendment,” as though we knew exactly what it meant. But when you look at it, the First Amendment breaks things down in a way that people might not think about, but that has proven meaningful. Would you tell us about that?

Kia Rahnama: “Most Americans believe that they have a very robust right to protest…but the courts haven’t felt that way necessarily.”

KR: Sure, yeah. So one of the main reasons I was interested in writing about this was that I’m genuinely very interested in the constitutional rights that I like to say are kind of like phantom limbs, in the sense that Americans kind of sense their existence, they go about their lives thinking that they have certain rights, but, as you mentioned, in a lot of these instances, the legal backdrop that’s been offered by the courts has actually gone the other way, and has diminished a lot of these rights to a point where they’re almost nonexistent.

I feel like the right to protest, today at least, is one of those rights, where most Americans believe that they have a very robust right to protest, and if you ask them if they know about the First Amendment, they would probably say, “Oh, this should come from the right to peacefully assemble as it’s listed in the First Amendment.” But as I mention in the piece, the courts haven’t felt that way necessarily. And over the past half century or so, they’ve pretty much diminished the right to assembly to a level where it’s provided the backdrop for all of these things that people are observing in the news these days that [are] offensive to them, about how protesters’ rights are essentially stepped on; and they seem to be shocked to see how much power and control the police officers have to essentially interrupt and interfere with peaceful protests.

JJ: Let’s talk about the founders, if we can go back for a minute. The First Amendment distinguishes between freedom of speech and freedom of assembly. They’re two separate things in the amendment, and presumably that’s because they knew there was something different about them.

KR: Right. And I think there is enough evidence to say that the founders who supported adding the phrase “right to peaceful assembly,” separate and distinguished from the right to free speech in the First Amendment, thought about it that way. They certainly thought that there was a difference between collective speech—as it would play out in a public platform, in the form of a street protest or a rally—and individual speech, so they wanted it to have its own listing in the First Amendment.

As history unfolds, obviously a lot of Supreme Court doctrine and jurisprudence ends up being framed by accidents of history, and the Progressive Era in the 1890s, 1920s, happened to be a very important timeframe for this right. There was a lot of labor unrest in America during the Progressive Era, and a lot of labor organizations picked up going to the streets, having their members armed; that was a moment in American history where the courts, by just accidents of history and what was the demographic, the people who were on the court at that time, they took a huge step backwards. And they essentially said that they thought the right to peaceful assembly in the First Amendment doesn’t necessarily give a blanket protection for protesting in the streets.

They defined it to protect ancillary rights, like the right to association, and later on, lobbying, and all these things that people wouldn’t necessarily naturally associate with the right to free assembly, and they decided to relegate the conduct of protest in the streets to freedom of speech. They essentially ended up saying, “We’re going to treat this as a kind of individual speech.” And since then, since the right to protest has been relegated or subsumed, they’ve even refused to develop its own legal standards for it.

So a lot of the police conduct that takes up the news headlines these days—there are lawsuits going on with a lot of organizations, like Black Lives Matter and ACLU, but even the litigators in these cases know that there’s a complete void. The court has even refused to fashion concrete legal standards about what the rights of the protesters are.

JJ: Right. And the path that rulings and conversation and discourse around freedom of speech have taken, and that of freedom of assembly, have been divergent to the point that, as you explained in the piece, when we talk about a “chilling effect,” the court has acknowledged that when it comes to speech, but not when it comes to assembly?

KR: Right, and I think this is one of those gaps that would make sense to most people. A lot of the coverage in the news about the police conduct and show of force, a lot of these [reports] bother people because they think, “It seems like the police are just trying to create an atmosphere of fear.” The tactics are draconian, just to essentially send a message to people who would go on the street that your conduct is gonna receive a really harsh reaction.

JJ: Maybe you should stay home.

KR: Yeah, you should stay home. And as it happens with individual speech, the courts have actually tried to find a solution to this, which is, you refer to it, the chilling-effect standard. They’ve said, essentially, the government doesn’t necessarily need to prevent you from saying something for it to violate your rights of individual speech. It’s enough that they do something that might put you in fear of speaking about something, even if they don’t have the intention of punishing you. It’s enough for that to violate your freedom of speech.

So the example I would give is, if today the US government were to say, “We’re gonna survey social media accounts and we’re going to see who’s talking positively about antifa, or this organization and that organization.” And let’s say the government claims that, “We’re not doing this to stop anyone from speaking in those terms; we just want to gather demographic information.” So that wouldn’t necessarily stop anyone from speaking on the subject online, but it would be unconstitutional under the chilling effect doctrine, because it will reasonably put citizens in fear of saying something, because they would say, “Well, the government is monitoring my speech; even if they’re not going to stop me, I’m afraid of the future consequences.”

And I feel like that is a standard that, on its face, could reasonably be extended to the right to protest, essentially, if the courts were to stay true to their words. Because it’s reasonable to see or conceive a situation where a lot of people who would be future attendees in these protests are reading all of this news about permanent injuries for protesters that have attended these rallies, and have been subject to crowd control tactics or surveillance tactics, things that will essentially have an impact going on after the rally in your life. And they could very conceivably create an atmosphere of fear where a lot of people who would potentially attend these rallies or events in the future would just not do so, out of fear of its consequences.

JJ: Or, for example, things like the Tennessee new law that’s going to categorize some protesters, those who “camp out,” as felons, so they’re going to lose their voting rights in the future. They’re not really trying to leave any mystery here.

Finally, going forward, we see the voids, but what needs to happen, and what sort of case could bring about the changes that would be helpful, or what do we do, shy of the Supreme Court, to bolster this right to assembly?

Pro Publica (7/16/20)

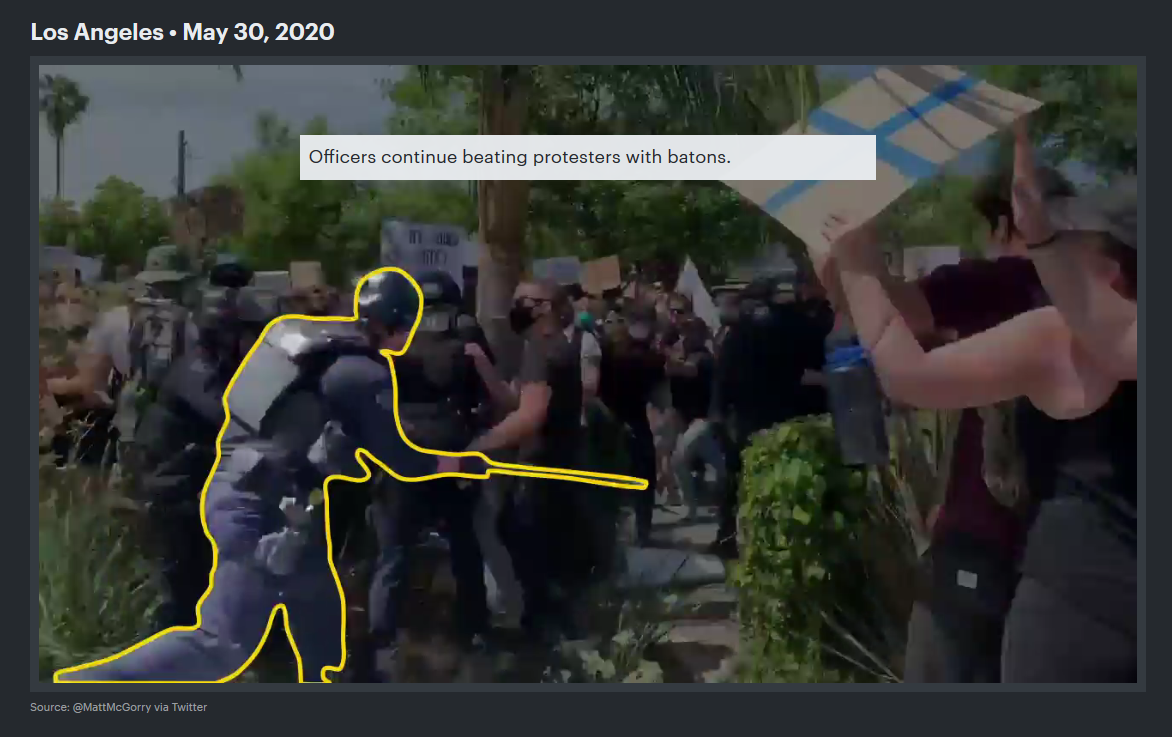

KR: I think journalists actually play a huge role here. One of the most common comments that I received to the piece was that a lot of people were saying, “Well, how could you say that? A lot of these protests are riots,” or “They’re not peaceful.” And I think journalists have a role here in doing a better job of investigating. I cited an independent study from ProPublica in the piece, which showed instances where harsh police tactics were directed at isolated individuals at times where the crowd didn’t seem to be rowdy at all. And harsh police tactics essentially ended up escalating the tension between the police and the crowd. I think it’s very important for the media and journalists to be cognizant of those scenarios, to shed a spotlight in these situations and say, “Well, here are the examples of cases where we can clearly see that the police tactics and the crowd control tactics contributed to escalating the situation.” And it’s important to not just take the cameras and film everything, once everything is escalated and both sides are obviously reacting to a more tense situation.

Documenting that; it’s also important for the journalists to try to trace individual police behavior that they see as unacceptable to the police precinct policies. I think the courts could definitely use the information that the journalists can gather in the situation by going to the police precinct, demanding access to the training records that they have for their police officers: “What is your established policy for crowd control? How do you train your officers to engage with the crowds? When do you allow them to use rubber bullets or tear gas or heavy weaponry?”

And if the journalists can get access to those records, I think the courts are going to have a lot easier time reviewing these cases, because it’s easier for them to review a concrete established policy of a police precinct, and say, “This is clearly unconstitutional.” Whereas, if it’s a police officer, a lot of times the courts just shrug these away and say, “You know, this was just one police officer acting on his or her own accord, and it doesn’t flow to the police department, so it doesn’t necessarily need our voice, or doesn’t feed our time, to go in and deal with the department as a whole.” I think the media and the journalists can play a very important role here in essentially clarifying the landscape for the courts.

JJ: We’ve been speaking with constitutional law attorney and writer Kia Rahnama. You can find his piece on “How the Supreme Court Dropped the Ball on the Right to Protest” on Politico.com. Kia Rahnama, thank you so much for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

KR: Thanks very much, Janine.

PrintCounterSpin | Radio Free (2020-09-17T22:44:15+00:00) ‘The Court Has Refused to Fashion Concrete Legal Standards About the Rights of Protesters’. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/09/17/the-court-has-refused-to-fashion-concrete-legal-standards-about-the-rights-of-protesters/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.