You can see Kryvyi Rih’s new slogan “A city as long as life itself” wherever you go in Ukraine’s longest town – posters in the park, street advertising and trolleybuses. And the slogan suits Kryvyi Rih – it takes a while to get from one end of the 120km-long city to the other. The trolleybus drives for an hour before it stops outside the factory administration building of the Kryvyi Rih Iron Ore Plant.

Here, miners and their families are holding protests every day in support of their colleagues, who have spent nearly two weeks 1.5 kilometres underground – fighting for wage increases and decent working conditions. Ukrainian website Political Critique reports from the protests last weekend.

“Guys, is there anyone from the Lenin mine here?” a male voice calls out from the crowd. A few people respond, raising their hands or shouting out “Here!”

This is the old name for the Ternovska mine, which is part of the Kryvyi Rih Iron Plant – the biggest iron ore mining enterprise in Ukraine. Aside from the Ternovska mine, there’s also the Rodina (Homeland), Gvardeiska and October mines.

On 3 September, miners at the October mine refused to leave the mine after their shift, demanding higher wages, better working conditions and management’s resignation. Four days later, three other mines joined their protest, and there’s now more than 200 people underground, although initially the numbers were around 400. Some miners had to come up due to problems with their health.

“This isn’t the first day. No one is speaking to us. We don’t know what to do,” one woman tells me, checking her hair nervously. Her husband is one of the miners still underground. We’re at a protest outside the management building, and a few minutes later she goes over to the microphone and calls on the crowd to shut down the unloading of ore from the mines – people should just “lie down on the rails”, she says. According to her, it’s the only way out of the current situation. After all, several of the mines are full of ore, which means management does not have to propose any kind of dialogue. Other miners present do not agree with her position.

“Yesterday I spoke to the boys at Gvardeiska. They said that there’s enough ore to last till New Year.”

“All the ore is at the Lenin mine, there’s no ore at Gvardeiska.”

“The Lenin mine is empty!”

Sergey Movchan

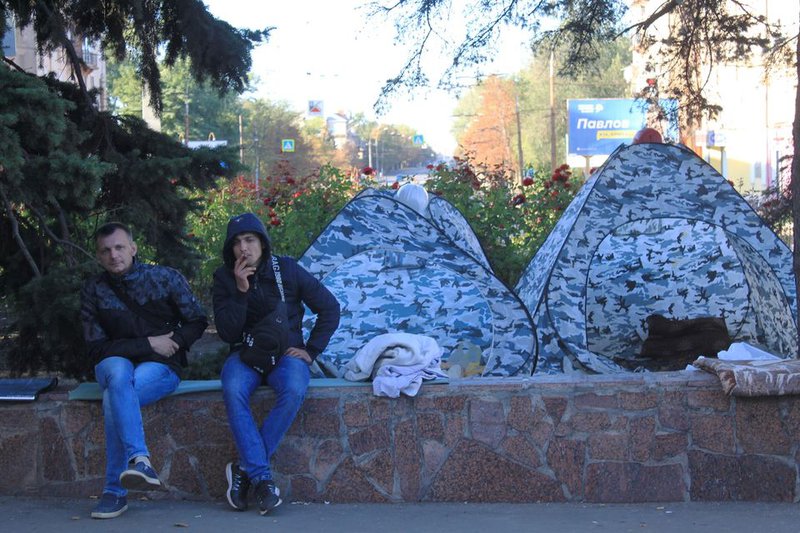

Sergey MovchanPeople hold rallies outside the Kryvyi Rih Iron Ore Plant office every day. Some workers even stay overnight, in two tents set up under some nearby pine trees.

There’s a PA system set up on the steps in front of the building, and a microphone and orange miners’ helmet on top of it. Between three and five in the afternoon, it’s an open mike – anyone can say anything. People involved in the protest come up and take their turns – they share news, discuss how to get their situation across to the public, and their plans to travel to Kyiv to meet people in parliament. Sometimes they argue. There’s a lengthy discussion about the fact that Ukrainian media are boycotting their protest: when miners contacted Ukrainian newsrooms, the media refused to cover their protest on the grounds that the topic isn’t interesting. “New roads are being opened, electric scooters are being launched, there are fires. There’s everything you want, but not us,” one man declares sadly.

“Let’s put up flyers, we’ll get the news across by word of mouth!”

“Everyone already knows about this in our city. What are you talking about? You might as well as throw flyers from a helicopter.”

“Go on then!”

From time to time, the miners bring up Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyi, who was born in Kryvyi Rih. “They’ve brought his hometown to its knees, why doesn’t he come here?”

“At this rate people will still be down there until New Year. We’ll have to send a Christmas tree and presents down there,” others joke.

Later, an electrical engineer from the Gvardeiska mine takes the microphone and passes on a hello from colleagues underground: “They’re not losing hope, they joke: who isn’t getting enough to eat up there, perhaps you guys need one of our sandwiches? Don’t give this fight up now you’ve come out. Glory to the miners, for God’s sake.”

Nearly all of the miners present recall the events of 2017. Back then, miners refused to come up after their shift and, just like now, demanded monthly wages of $1,000. According to the workers, after these protests, management raised wages by 10%, then 7%, although they promised a 50% raise. But then mine workers lost all their additional payments: “They just stopped paying us, that’s it. People have had enough.”

Now, the miners say, they’ve been forced to remain underground due to unacceptable working conditions, low wages, management’s attitude to workers, a lack of necessary tools and the fact that Ukraine’s official list of harmful professions has been cut – which allowed miners to retire early due. Miners also want to change the wage system to an hourly rate. Their wages currently depend on their productivity – for every metre they mine, they receive between 30 and 60 hryvnya (£0.80-£1.60), depending on the mine.

“How many metres do I have to mine in order to buy a boiler?” one of the miners standing nearby asks.

Kryvyi Rih Iron Ore Plant | Sergey Movchan

Kryvyi Rih Iron Ore Plant | Sergey MovchanLyubov, now 41, has been a machine operator at the plant since she was 19. She took the job for personal reasons – she really needed money at the time, and thought that it would be just for a few years. But in the end she stayed. She tells me that the average wage for women at the mine is between 4,000 and 6,000 hryvnya (£110-£165), and the conditions are far from brilliant. “There’s mushrooms growing in our mine, constant drafts, it’s wet. And what kind of lifts do we go down in? Everything has rotted through, rusted, covered in water.”

If everything depended on their labour, even if it is hard work, then the miners claim they could make decent money. The problem, they say, is that the mine is a complex mechanism that depends on the efforts of many people. The production rate depends not only on miners, but tools and materials, and the way labour is organised by mine management. And the latter, the miners claim, is doing everything to save money on wages.

“You have a plan: you need to cut through 200 metres. You start getting to 100-150, and they stop taking away the material you’ve dug. It’s happened that there’s no explosive in the mine for two or three days, and that could be nine shifts. If you don’t finish the plan, you don’t get paid,” says Alexander, a miner at the Rodina mine.

He asks me to call him Sanya, and he doesn’t want to be photographed – he’s afraid of getting into trouble with management. A few moments later he comes over with his telephone and shows me a message on Viber – he’s been paid. “Look at how much I make. My wife makes three times this.”

Sergey Movchan

Sergey MovchanThe miners talk about management at Kryvyi Rih Iron Ore Plant with open hatred. “They think we’re slaves, like a herd of cows. Then they try and blackmail us: ‘If you want to get paid something, guys, then you need to work weekends too.’ You don’t know how much you’re going to get paid at the end of the month. They can just tell you: ‘There’s no money’.” One of the protesters delves into his telephone to show me a clip where plant director Serhiy Novak is heard to say that he does not “give a shit” about people working at his mine.

After the open mike ends, the protesters start talking in groups. Next to the tents there’s a couple of big guys – two of them are quite young, perhaps 25, the rest are older. Initially they are quiet when it comes to sharing their problems, pausing for a long time before answering. But after a few minutes it’s hard to stop them as they interrupt one another.

Eduard | Sergey Movchan

Eduard | Sergey Movchan“You feel ashamed to say you work in a mine,” says Eduard, who works in the water management system at Oktyabrskaya.

“When they ask you about your wages, and you say it’s 9,500 hryvnya [£260], people look at you as if you’re crazy. How does that work: to go 1200 metres underground for that kind of money?”

“In 2012-2013 I was getting 1,300 euro a month at the old exchange rate,” says Alexander, who sinks shafts at the Rodina mine.

“I went to Egypt, my wages were enough – 1,300 euros for the trip. If you want a holiday at our seaside here in Ukraine, you have to work really hard.”

“There’s no point even talking about holidays – you have to feed your family, shoes, clothes and get to work. If your monthly utilities payments are 3,000 hryvnya [£82] in winter, and your wages are 9,500, then what can you do.”

“In winter you never even see the sky. And what for? Before at least the wages were enough. And now you think: why did I even get a job at the mine?”

The miners agree to have their pictures taken immediately. “What is there to be afraid of any more?”

Under a new memorandum, factory management has promised to raise wages for underground workers by 10%, and those working above ground – by 25%. But no one wants to agree to the new conditions. Everyone complains about the state of the equipment they have to work with, and the fact they have to buy their own tools when their wages are not enough as it is.

When it comes to the “lads” who have stayed underground, the miners talk about them with pride and concern – it’s a long time to spend in a damp, bare environment. “The only place you can wash is in the mine water, and you can find the whole Periodic Table in there. In terms of the comforts of civilisation, there’s only food and water.”

Olga Potapenko is a lively woman with light hair – her husband has been in the Rodina mine for six days now.

“They went to work on Monday and we haven’t seen them since,” she says. “We talk through the radio operators, who tell us when our husbands want to greet us. We don’t have any more communication. They say that everything’s fine and that no one wants to come up. When we started coming to these protests, the guys were happy, and my husband even sent a message that he feels my support.”

Everything starts to quiet down by evening, and people start to go home – until tomorrow, when the protest outside the factory management building will start again. The only people who stay are those who will spend the night in the tents. On the bus later, two men look over at the protest and whisper:

“What’s happening there?”

“It’s the miners striking again.”

Tents next to the mine administration building | Sergey Movchan

Tents next to the mine administration building | Sergey MovchanThis text was prepared as part of the School of Social Reportage project, with support from the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation in Ukraine.

PrintAlina Stamenova | Radio Free (2020-09-17T00:00:00+00:00) Why miners in Ukraine's longest city are holding an underground strike. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/09/17/why-miners-in-ukraines-longest-city-are-holding-an-underground-strike/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.