Racism and laïcité

Two additional intertwined themes have to be addressed if one wants to get a handle on what is going on and why things are steadily going downhill at this particular moment in France. The first is the all-pervasive racism in France that has increasingly taken on the form of demonization of Muslims while never abandoning its traditional racist roots. The second is the problem of laïcité. One has to use the French word rather than the translation ‘secularism’ because what most English speakers understand by secularism is not what is currently meant by those brandishing laïcité in France.

One could argue that these have been brought together because, cynically, Macron sees it as a good way to get re-elected. There is a clear element of truth in this. Half way through his presidency he switched gear early in the summer, bringing in a new prime minister and reshuffling ministerial portfolios declaring they had 600 days to get things done before the next presidential poll.

A key figure in the changes is the Minister of the Interior Gérald Darmanin, someone for whom the issue of Islam is personal. His grandfather was what the French termed a harki, one of the locally recruited troops used by the French in the Algerian war. Many were killed in the aftermath of the French withdrawal. Tens of thousands fled to France where for decades they lived harassed lives in refugee camps, not wanted by any side, neither the victors nor the vanquished.

He has been given free rein by Macron to talk up confrontation, not just with a tiny Islamist terrorist fringe but with the Muslim community in France as a whole. He had always, he told us after Paty was beheaded, disagreed with the presence of halal food sections in French supermarkets.

What relevance the one had for the other is impossible to understand unless you take those two intertwined strands in French life.

Racisms

The most recent survey of the experiences of those confronted by racist prejudice and discrimination, Racismes de France, was published just this October[1]. The different authors draw together the evidence of the way discrimination and prejudice are at work across French life whether at school, in where you live, the work and pay you get or how the police treat you.

The most troubling evidence offered is the way in which the public authorities may accuse those who seek to point up these facts of being anti-Republican or in league with extremists, exactly the argument used these last few weeks against organisations that have criticised the pervasive Islamophobia in the country and the public practices that discriminate against Muslims.

A forceful essay on Communitarism: A spectre that haunts France argues that “The transformation of the victims of these social inequalities into the guilty party helps to obscure the development of a pyramidical society” in which the rich at the top live their separate lives in gated communities or Caribbean isles while the objective reality of social and racial segregation at the bottom of the pile is seized upon for a discourse about “the danger of communitarism” creating “a fantasm based upon fear” as in the term “the Republic’s lost neighbourhoods”.

This is the France in which 44 per cent of respondents in one major survey in 2018 ticked the box for “Islam is a menace for France’s identity”. Which is where the second theme, laïcité comes in.

Laïcité

It has its roots in the late nineteenth century contest against the role of the Catholic hierarchy in French life. Consolidated in a law in 1905, the end result was the exclusion of the Catholic church as an institution from controlling, or trying to control, everyone’s lives. The target was not individual Catholics, but the institution of power represented by the church and its hierarchy.

To grasp why this has gone wrong in modern France and its conflicts another good book to plunge into is La laïcité falsifiée, Laïcité falsified, by Jean Bauberot[2], one of the main established authors on the general topic. Published just before the terror attacks in 2015, its argument is direct.

He opens immediately with the statement: “The secular left finds itself put to the test. Laïcité, which seemed to constitute an essential element of its identity, is today brandished as a beacon by the hard right and the extreme right . . . Between the winter of 2010 and the autumn of 2011 the nature of laïcité profoundly changed. Marine Le Pen proclaimed herself champion of laïcité and played at rushing to rescue the law separating religion and the state.”

I remember watching the live broadcast of the speech she gave to a Front National conference at which she was declared leader, replacing her father Jean-Marie. She adopted a series of policy points that were of the left – playing Tony Blair’s triangulation game with deft swiftness – and then took on Islam. Its very presence appeared to be an affront to laïcité.

As Bauberot notes, the response of the ruling Gaullist Party of Sarkozy was to propose a “new laïcité” that trailed behind on the road Le Pen had carved out. Since then much of the traditional centre left has been dragged into line.

Let’s just take two moments to compare this “new laïcité”, now shared across much of the political spectrum from the far right to the centre left, with the old.

The starting point for the modern contest with the life of Muslims in France is usually taken as the decision over 30 years ago by two young students to go to school in their town of Creil to the north of Paris wearing hijabs. As the row over this developed, the then government sought the advice of the Council of State, the highest court when it comes to interpreting the law. For the council, the action by the two students was quite compatible with laïcité. In 2004 the matter was resolved by a law banning such things.

Fast forward to today. On 2 November, school students across France returned to their classrooms, despite the Covid lockdown, for lessons marked by what the Education minister calls a “reinforcement of the values of the Republic”. In supposed honour of a teacher, murdered because he showed the Charlie Hebdo cartoons of Mohammed to his pupils, all school students will now be shown them.

What would Jean Jaurès say?

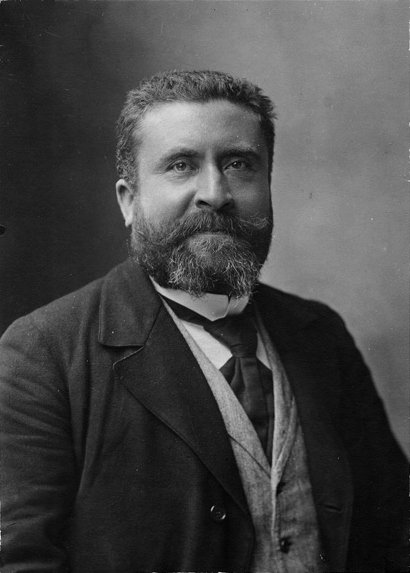

They were all given a reading from the writings of Jean Jaurès, one of the great founding figures of the modern left in France and himself a victim of murder most foul at the hands of a right wing nationalist as the war clouds were gathering in late July, 1914. The text was about education, but a crucial passage had been cut out by the Ministry of Education. No wonder when you look at the educational policies being enforced under Macron.

Jaurès’ censored passage, censored by a regime prating its undying commitment to freedom of speech, was this: “What a deplorable system we have in France with these exams at every turn that suppress the initiative of the teacher and the real content of teaching by sacrificing the reality for the appearance.”

Amid the calls for “war-time laws” (that’s from Marine Le Pen), for a new punishable offence of “separatism” (that’s from Macron) or a ban on “Islamo-Leftism” (that’s from possible presidential candidate for the mainstream right, Xavier Bertrand) Olivier Faure, the Socialist Party leader, offered this thought for those students and the Republican values they are to be taught:

“We need to be clear. For example all those who give themselves the right to contest a teaching or teaching in general must be taken before the courts every time. We, the left, have sometimes considered that toleration in respect of the weakest should also lead us to a form of toleration in respect of that which was intolerable. We are at a turning point. Too many arsonists are disguising themselves as fire fighters.”

To which one can only say, quite so. What Jaurès would have said is probably unprintable.