Heading into the final stretch of the 2006 midterms, House Democrats were in need of an agenda. They had ridden the frustration at President George W. Bush as far as they could, and his mishandling of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and the occupation of Iraq had allowed them to skate by without offering a compelling countermessage. Rep. Rahm Emanuel, chair of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, had been pressing then-Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi to formulate some sort of vision the party could rally behind, though Emanuel wanted to make sure it wasn’t anything that sounded anti-war, socially liberal, or hostile to business interests.

Many of the candidates he recruited around the country refused to condemn anything but Bush’s handling of the war and were far to the right of the typical House Democrat. Pelosi had put him off, later telling Molly Ball, Pelosi’s biographer, that she hadn’t wanted to put a message out too soon in the campaign and see it drowned out.

In late July, the party finally released its vision, calling it “A New Direction for America” and putting forward six policy ideas under the cringeworthy slogan “Six For ’06.”

Among those six incremental reforms was a promise that Democrats would allow Medicare to negotiate lower drug policies with pharmaceutical companies and use the savings to expand Medicare benefits. In November 2006, they won the House back for the first time since 1994.

Now, 15 years later, Democrats are staring at an opportunity to actually make good on that promise. Despite reports that the provision has been stripped from the final package — it was not included in the House bill released Thursday afternoon — Democrats in Congress say the fight isn’t over. “The negotiations are still going on,” said Sen. Catherine Cortez-Masto, D-Nev., Thursday evening. “It’s the number one issue I hear about in Nevada. And rightly so, we have to reduce drug costs. Negotiation is a key part of it.”

On Thursday afternoon, House progressives again beat back an effort by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the White House to split the bipartisan infrastructure bill from the broader Build Back Better Act moving through Congress under the majority-only rules of reconciliation. The progressive caucus and their allies in the Senate say they’ll use the leverage they’ve preserved to fight to get some form of drug-pricing legislation back into the bill over the weekend. Pelosi, too, is pushing to reinsert something. At a press conference Thursday, she said that there were elements she still hoped to see survive, and as the architect of the political strategy of centering drug prices in Democratic elections, her credibility is on the line. The battle represents the collision of two elements of Democratic politics that are fundamentally in conflict: what they tell voters in order to get elected, and where they get the money to broadcast that message to voters.

Since 2006, they have told voters that, given the opportunity, they’ll take on the power of Big Pharma and force the industry to lower drug prices, so that Americans are no longer paying vastly more than people in any other country on Earth. At the same time, they have been substantially bankrolled by the very industry they have promised to take on. Fulfilling their promise to voters requires butting up against the financial interests of a powerful wing of the party. But breaking their promise threatens their ability to ever again promise action on an issue that is a driving concern for voters.

Just one week after receiving the speaker’s gavel in January 2007, following the Democratic sweep the previous year, Pelosi made good on her end of the promise, leading House Democrats in passing the drug negotiation bill — which promptly died thanks to an inability to surmount a filibuster in the Senate.

Had it passed the Senate, there’s no reason to think Bush would have signed it into law, but the bill’s fortune’s changed when Barack Obama was sworn in as president in January 2009 with a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate by July of that year. But his White House quickly moved to cut a deal with Big Pharma instead, promising not to push for drug price negotiations in exchange for the industry agreeing not to oppose reform and to cut $80 billion in costs over 10 years. Pelosi vowed that she wasn’t bound by the deal, but no drug price negotiations were signed into law.

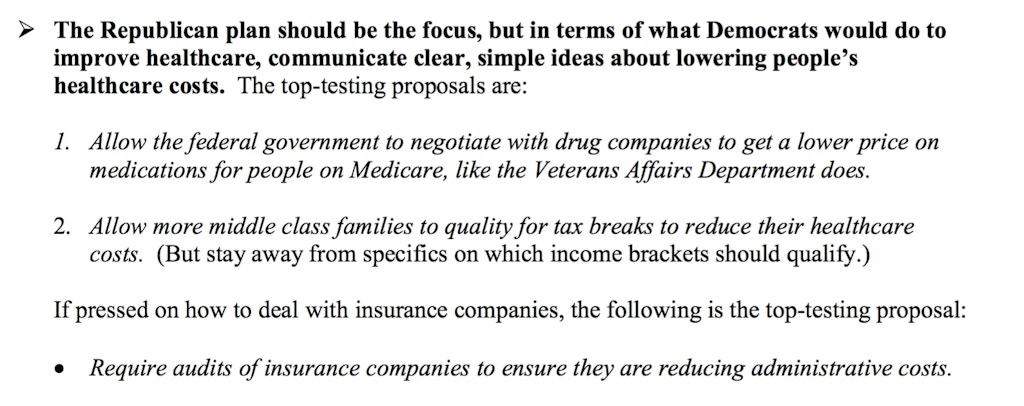

In 2018, as Medicare for All surge in popularity, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, spying a shot to finally regain the House, warned candidates not to run on single-payer or any big sweeping reform, urging them instead to focus on lowering drug pricing, citing internal data that it polled better.

The memo to candidates said that the top-testing recommendation was to allow the government to negotiate lower drug prices. Democrats that cycle and in 2020 made lowering drug prices their central campaign issue on television ads. One of the Democrats who flipped a Senate seat in 2018, promising lower drug prices, was Kyrsten Sinema.

The 2020 elections put Democrats in the strongest position in a decade to finally enact their policy agenda. While holding slight majorities in the House and Senate, they could pass long-promised drug pricing reform using the budget reconciliation process that allows them to avoid a filibuster from Republicans.

Upon entering the White House, President Joe Biden made empowering Medicare to negotiate down prices a central part of his American Families Plan. Democrats crafting a reconciliation deal to implement that plan eyed the cost-saving measure as a way to pay for expanded Medicare coverage, achieving two wins in one.

But the plan was opposed by pharma-backed Democrats, especially Sen. Bob Menendez of New Jersey, whose state hosts more pharmaceutical companies than any other state in the country. In a sign of the internal party dispute to come, Menendez offered his own drug cost reform proposal earlier this year that would cap seniors’ out-of-pocket expenses while preserving the industry’s massive profits and denying Medicare beneficiaries the more affordable prices that customers in other countries pay.

In the House, the drug pricing measure was defeated in the Energy and Commerce Committee, thanks to the defections of three Democrats: Reps. Scott Peters of Ohio, Kurt Schrader of Connecticut, and Kathleen Rice of New York. Peters and Schrader are known to be bankrolled by and loyal to Big Pharma, and Rice is Peters’s closest ally in the House. It was her first year on the powerful committee: She had battled Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., for the seat, and the party’s steering committee had given it to Rice in a landslide.

In the Senate, Sinema has refused publicly to support the provision and is said to oppose it in private. She again declined to comment when approached Wednesday by The Intercept in the Capitol. Sen. Angus King, I-Maine, told reporters this week he had not even heard from Sinema about her position but cannot understand her rumored opposition. “All it is is making Medicare consistent with the [Veterans Affairs Department] and Medicaid, which have had this … negotiated discount for many years,” he said.

Meanwhile, Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., admonished lawmakers unwilling to support reform, telling reporters earlier this month: “It’s beyond comprehension that there’s any member of the United States Congress who is not prepared to vote to make sure that we lower prescription drug costs.”

The pharmaceutical industry is “spending hundreds of millions of dollars trying to make sure that they continue to make outrageous profits to charge us, by far, the highest prices in the world for prescription drugs,” he said. “So this is not just an issue of the pharmaceutical industry. This is an issue of American democracy. And whether or not the United States Congress has the ability to stand up to incredibly powerful special interests like the pharmaceutical industry.”

Sanders’s observation is perhaps an understatement. The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the omnipresent trade group and lobbying arm for drugmakers, spends over $500 million a year shaping policy and mobilizing the pharmaceutical industry to speak with one voice when it comes to any attempt to regulate drug prices.

The restriction on Medicare negotiating drug prices dates back to the creation of Medicare Part D in 2003, a Republican plan that Bush White House adviser Karl Rove believed would make seniors a permanent bloc of Republican voters. The legislation, opposed by Democrats, added prescription drugs as a benefit of Medicare, a major advance that has been important to improving the health of seniors — both personal and financial. The law was also a major gift to pharmaceutical companies and included a provision that would bar the Health and Human Services Department from negotiating lower prices.

Despite the ostensible ban on lobbyists’ money, drug industry money continued to flow into the Democratic Party.

The drug industry’s role was sharply highlighted on the campaign trail by Obama when he first ran for president. “First, we’ll take on the drug and insurance companies and hold them accountable for the prices they charge and the harm they cause,” said the Illinois senator on the trail while campaigning in Virginia. “And then we’ll tell the pharmaceutical companies, ‘Thanks but no thanks for overpriced drugs.’ Drugs that cost twice as much here as they do in Europe and Canada and Mexico. We’ll let Medicare negotiate for lower prices.”

Obama pointedly banned drug industry lobbyists from donating to his campaign and villainized them on the stump. But even at this seemingly high-water mark for reform, at every step of the way, the drug industry money continued to flow into the Democratic Party, with the explicit goal of buying influence and curbing any prospect for price-cutting policy becoming law.

Despite the ostensible ban on lobbyists’ money, non-registered drug industry representatives poured cash into the Obama campaign through individual contributions. Pfizer officials paid $1 million for skybox seats to watch Obama accept the Democratic nomination in Denver, at a party convention made possible by donations from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Amgen, and Merck. The chief executives of the largest drugmakers mingled with Democratic National Committee officials at invitation-only events. The Center for American Project Action Fund, the think tank that was considered Obama’s administration-in-waiting, accepted $265,000 from PhRMA during the campaign.

The following year, during the desperate legislative battle to pass what became the Affordable Care Act, PhRMA lobbyists won the deal that kept Medicare drug price negotiation or any other similar price cap on lifesaving drugs out of the law. In exchange, Democrats were promised $150 million in ads designed to boost public support for health reform. The agreement minted the chief PhRMA lobbyist, former Rep. Billy Tauzin, a special $11 million payday for his role in shepherding it through Congress and the White House.

The Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision in 2010 radically reshaped the political landscape for pharmaceutical companies. Drug firms were already routinely ranked among the largest industry donors to candidates and political action committees. Pharmaceutical companies and their representatives donated regularly to lawmaker foundations, including the foundation run by former Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, and by current Majority Whip Jim Clyburn, D-S.C.; as well as the Congressional Black Caucus, the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute, and other nonprofits and think tanks associated with policymakers.

But the court decision opened a new financial sieve for drug firms to dominate elections. The largest drug lobby group — PhRMA — went from routine $1,000 checks for individual lawmakers to dumping seven-figure sums of largely undisclosed corporate cash into the coffers of dark-money groups and super PACs. American Action Network, a GOP campaign arm that can raise and spend unlimited amounts thanks to the court decision, took in $14.6 million from PhRMA.

In short order, pharmaceutical firms made sure that any close congressional election would rely heavily on funds tied, at least implicitly, to a demand that drug pricing regulations stay off the table.

The Democrats lost the House in 2010, while Republicans swept statehouses across the country and used their newfound power to gerrymander a durable majority. Even as Democrats won the popular vote for the House over the next decade, they remained locked out of power. The Obama administration, hobbled by its previous losses, did little to fight the pharmaceutical industry on any major cost-related issues.

But the salience of the problem began to make waves again in 2015 and 2016, as controversies around astronomical drug price increases absorbed headlines. Turing Pharmaceuticals, led by a young investor named Martin Shkreli, purchased the patent rights to a crucial parasitic infection pill called Daraprim, and hiked the price by 5,000 percent overnight. Valeant Pharmaceuticals, a darling of Wall Street, spent virtually nothing on research and development, and simply purchased patents and hiked prices on a range of drugs.

States attempted to push back but were crushed by the tidal wave of pharmaceutical money. In 2016, a California ballot measure attempted to tie the price of Medicaid drugs to the rates paid by the Department of Veterans Affairs — a workaround to lower prescription via collective bargaining. The drug industry plowed into the state, financing the most expensive ballot campaign in history at that point (only to be surpassed by Uber’s Proposition 22 in 2020 over driver classification) to pressure voters into opposing the law. Groups typically aligned with Democrats — such as the NAACP, San Francisco’s historic LGBT Democratic clubs, and longtime Latino civil rights organizations — accepted consulting fees and grants from drug companies that year, and endorsed the drug industry-backed campaign to defeat the ballot measure. Drug industry-backed ads featured an array of Democratic organizations they had funded as they persuaded voters to oppose the measure — which went down in defeat.

During the 2020 election, PhRMA gave another $26.4 million to the Congressional Leadership Fund, the super PAC associated with House Republican leadership. PhRMA also financed groups for Democrats, including the major super PACs tied to party leadership and Center Forward, a dark-money group that supports moderate Democrats.

Democrats had promised to enact reform for so long, Sanders said, and had so much public support that failing to deliver would raise the question of what the purpose of electing them was. “And this is an issue of not just lowering prescription drugs. It’s whether or not democracy can work. And if democracy cannot work, if we cannot take on the pharmaceutical industry, why do you go out to ask people to vote?” Sanders asked. “Why do you ask them to participate in the political process, if we don’t have the power to take on a powerful special interest?”

This content originally appeared on The Intercept and was authored by Ryan Grim.

Ryan Grim | Radio Free (2021-10-29T14:57:15+00:00) Democrats Find Their Big Pharma Bag Is Making It Inconvenient to Take On Big Pharma. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2021/10/29/democrats-find-their-big-pharma-bag-is-making-it-inconvenient-to-take-on-big-pharma/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.