This article is part of a dossier in partnership between SyriaUntold and openDemocracy’s North Africa, West Asia page, exploring the emerging post-2011 Syrian cinema; its politics, production challenges, censorship, viewership, and where it may be heading next.

For decades, cinema in Syria was subjected to particularly harsh censorship by the Assad regime. The Soviet-influenced ideological compass of the Ba’ath Party strongly believed in the power of cinema to shape and ignite hearts and minds, to its own detriment.

Filmmaking was restricted to official productions from the National Film Organisation, which produced no more than two films per year, commissioned to a handful of regime aficionados operating under strict regime censorship and ideological agendas.

Even foreign films screened in theatres inside Syria were heavily censored and most “western” or Hollywood films were not allowed into theatres, with the sole exception of the five-star Al-Cham Hotel’s theatre in the commercial center of the capital, in the 1990s.

The 2011 uprising provided a catalyst for independent voices to speak out and break from the limitations on film production imposed by the regime, thanks to affordable technology, global interest and overwhelmingly strong subject matter.

Most of these emerging filmmakers resorted to documentary films, partly due to their lower production budgets, but also due to the market demands of the news industry, and the almost instinctual need to document what they witnessed.

Feature-length fiction films remained predominantly pro-establishment, in line with the regime narrative. Although a few attempts at short fictions were made by young and independent filmmakers, shooting in extreme and precarious conditions. However, not many harnessed the same International acclaim as did their documentary counterparts.

The year 2018 witnessed the first ever Oscar nomination for a Syrian film, helping Feras Fayyad’s documentary film “Last Men in Aleppo” break out of the more elite festival realms within Europe and into globally accessible platforms such as Netflix. Last year, Talal Derki’s “Of Fathers and Sons”— another documentary about the family of a hardline Islamist militant in northern Syria—followed suit, and was also nominated for an Oscar. Waad al-Khatib’s “For Sama,” which tells the story of the fall of Aleppo from a young mother’s perspective, has won over 25 international awards so far since its release earlier last year—and also made it to this year’s Oscar nominations.

Despite what many call a global news fatigue with Syria, powerful films continue to emerge.

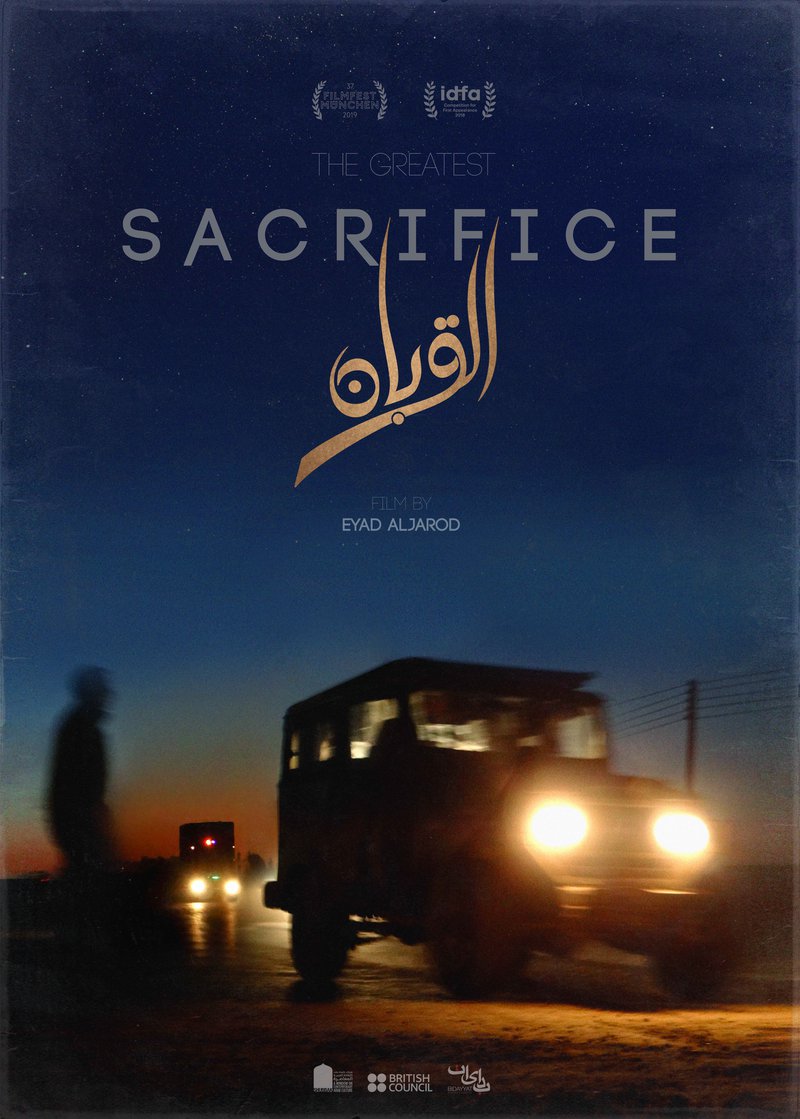

The Syria Untold team, along with our partners at openDemocracy, have had passionate discussions about the current status of Syrian cinema today, which resulted in this autumn’s long dossier on emerging Syrian cinema: its politics, its production challenges, its censorships, its viewerships, and where it may be heading next. One such discussion we attended in the previous edition of the International Documentary Film Festival of Amsterdam (IDFA), during which a few Syrian and Syria-related films were screened, took place between Syrian filmmakers Dalia al-Kury (Privacy of Wounds), Iyad alJaroud (The Greatest Sacrifice) and Layla Abyad (Letters to S.), who discussed the current status of Syrian cinema and some of the main challenges they themselves face in their work.

Exhausted audience?

Dalia: I come to IDFA and send a message to some Syrian friends suggesting we watch one of the Syrian films in the festival, but they are often reluctant and prefer to watch a foreign film about an issue they are less familiar with. So when we talk about the difficulties that an average Syrian encounters in accessing Syrian films, I have to ask: Do Syrians want to watch their own stories?

Eyad: During my work covering violent and painful events in Syria, I would question the purpose of documenting the violence, then screening it back to its victims once again. Wasn’t it enough to endure it? Why do we recycle the pain?

Dalia: But people want their stories to be told. They want to feel they have not been forgotten or forsaken and that someone out there is trying to tell the world about them and make sure they are not forgotten.

Eyad: I know, but it varies in my opinion based on the subject matter. These stories, these messages need to be sent out to someone else, to another group in another place. I don’t make films to change the world anymore, I don’t believe in that. Cinema is not going to change the minds of big politicians and decision-makers, they already have all the facts. But in my work I reach out to another human group, I try to interpret our stories and bring them closer to others by creating linkages and comparisons with similar events in their communities or history, so they can better relate on a human level. I also make films as a counter-rhetoric to the mainstream media coverage of our events, to make sure we write our own history and tell our stories.

Dalia: I don’t make films because I think they will create change in the world either, nor do I have any specific geographic group of audience in mind when I make them. I make films because I am intrigued by a specific human condition, and want to inspect it cinematically through the film medium. If the end film is good, it will communicate itself to whatever audience watches it.

In my latest film about [former] Syrian political detainees, I didn’t choose to make it because they are Syrians, I happen to be from the region so it’s very often my subject matter. I made the film because I am intrigued by how humans survive such trauma. There were some culture specific jokes and satire, one could say they might be hard for a foreign audience to understand, but I wasn’t going to take them out. Humour is a very important tool that humans use to survive their traumas and deal with them.

However, after the draft film was ready I screened it to a group of friends—one of them was Syrian—and they advised me not to include so much humour in the film because it could feel offensive to, say, the mother of someone who died under torture, to joke about political detentions. It was certainly not my aim to offend anyone, so I took out some of the jokes, but kept others. Humour is a fact of this human condition, and in the end, it is the [former] prisoners themselves joking about their own experience, not me. But I’m glad I had this test screening. It’s important to stay in touch with the communities you are talking about in your films.

Layla: Exactly! To me the lack of feedback, from the community itself, is a problem—but also the films not reaching them further complicates my work. Like you said, Dalia, people want their stories to be told. This was very clear and simple in Syria in 2011, in some areas all we had to do is show up with our cameras and people would rush to tell us their stories, or show us a bombed building, or take us to meet someone who was injured, etc. It was overwhelming. As time passed and they started to feel the world had already learned what was happening, but not helped much, in 2012 they started to be more reluctant to speak in front of the camera, especially with the threats on their lives if the regime caught them after it’s broadcast. As they lost hope in anyone in the world helping them stop the regime once they learned what it was doing, they lost faith in the role of media altogether, and in 2013, even local videographers would struggle to film mere buildings shelled by the regime in their own villages, because locals would not want them to post the documentation on YouTube, as a result of the regime using collective punishment and bombing against the villages that publish news about their plight. This made the camera a a target on two fronts, first by the regime and then by the very people whose stories you are trying to tell. Still, when a film is screened in a big festival abroad, Syrians would be enthusiastic, happy to see their stories on the big screen, and asking why the film didn’t also mention this or that. But when you lift up the camera and try to shoot it, no one wants to take the risk to be filmed.

The disrupted cycle

Dalia: So how do you guys deal now with the disinterest in producing Syrian stories nowadays?

I have an idea for a new film that was inspired by the experience of exile that a Syrian man I know is enduring, but I’m reluctant to cast him as the main character. In the end what he’s going through in his exile is shared by all other foreigners in the same country. If you’re Polish or Yemeni, the experience is the same.

Eyad: Was there a lot of interest before?

Layla: In 2011-2013, yes. But we deal with it because we have to. Our work was already very hard in every other aspect of the production.

Eyad: I didn’t really know of many funding sources back in those days. I shot two films between 2011-2013, it took five more years to finish the second one and screen it now!

Like I said, I make films as historic documents, to release myself from the burden of the witness. I was a math teacher before it all started—a cinema fan, but I had no previous training or experience in filmmaking. When the revolution started, I participated in demonstrations and graffiti writing and so on, and since I had a camera, I would document randomly what we were doing. As time passed and we realised how long this is going to last, not a matter of weeks or months, activities became more organised, everything in life around us changed so quickly; our friends, social dynamics, debates and interests, work, even the streets and city where we lived changed. I realised a mere Facebook page with photos on it wasn’t going to communicate this. This needed cinema.

PrintMaya Abyad | Radio Free (2020-01-13T23:00:00+00:00) New Syrian cinema: young and gasping. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/01/13/new-syrian-cinema-young-and-gasping/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.