” The Allies were gifted with time. Naval ships, vehicles, passenger ferries, fishing boats, yachts and boats owned simply for pleasure were assembled.

A handful of civilians even joined the mission, sailing out into the Channel voluntarily. Over the course of nine days this fleet, supported by British planes overhead, was able to rescue most of the troops.”

BBC News on ‘What actually happened at Dunkirk?’

Mid-May, Transformation published a stunning essay by Hanna Meretoja, warning against deploying the war analogy to describe the fightback against coronavirus. There have been some awful examples. Ministers keen to absent themselves from European cooperation had to hope that Matt Hancock’s invocation of the ‘Blitz’ on March 14 would persuade “some of the biggest names in British manufacturing” to supply a new British ventilator from scratch, quickly. But by mid-April, the FT was reporting that a potentially lethal procurement programme had sent manufacturers down entirely the wrong path for treating COVID-19 patients. Little competes with the Daily Mail headline for May 15 for sheer callousness, however, taking aim at the teaching unions and ‘imploring’, “Let our teachers be heroes. Magnificent staff across the nation are desperate to help millions of children get back to the classroom…”.

Another thought-provoking article left me wondering nevertheless what had happened to ‘Dunkirk spirit’ – that energetic revenant visiting UK bookshelves and screens from June 1940 to today. (As I wrote, the Express front page was busy pouring the latest libation: “Dunkirk spirit is with us… and will see us through coronavirus –.” ) This was an investigative piece by Peter Geoghegan and Tansy Hoskins, looking into the hiring of Deloitte by the UK government, one of the ‘Big Four’ accountancy firms, to manage PPE procurement. They had interviewed several manufacturers who responded to the urgent call, only to be frustrated by a delayed response and red tape. 8,000 emails in less than a month received an automated reply. But there was a failure to deliver, and questions were now being asked about Deloitte’s lack of knowledge of the “British textile industry, which has seen a flourishing of small businesses making high-volume fast-fashion items for a domestic market.” Those who had “avoided Deloitte’s centralised system” were reporting greater success.

Indeed, the message seemed to be, if you wanted to get something done, avoid the British state. Remember the 750,000 NHS volunteers who in just four days eagerly signed up for the “biggest call-out in England since the Second World War”? Over a month later the vast majority had yet to be called into action. You can read multiple online reports from frustrated and disappointed applicants. Self-organising has again done much better: witness the phenomenal growth of Mutual Aidgroups… 4,300 connecting an estimated 3 million people by mid-March. Meanwhile, Deloitte has also been making headlines for failings in helping the Department of Health roll out its national testing programme. Here again, there is incredulity at the priority given to a centralised system that runs the danger of bypassing all the very local knowledge that actually makes the difference: local authorities, local trackers and tracers who know the community, GP surgeries. And then there was the little matter of the government’s decision to plump for a centralised rather than a decentralised COVID App., leaving people far less control over their own data.

There is no dearth of people – groups of people, businesses small and large, experts, local authorities, trade unions, community organisations and whole communities willing to help. But it is as if the British state that Johnson presides over would rather do everything without them.

I am suddenly reminded of the ‘transformational state’ that Sir David Varney envisaged for big data Britain in 2020, in his 2006 report for the UK Treasury:

“All the people, children and young people, workless people and other customer groups can choose packages of public services tailored to their needs. Public, private and third sector partners collaborate across the delivery chain in a way that is invisible to the public. The partners pool their intelligence about the needs and preferences of local people and this informs the design of public services and the tailoring of packages for individuals and groups. Measured benefits, services and facilities are shared between all tiers of central and local government and other public bodies. The public do not see this process, they experience only public services packaged for their needs.”

So here is the great British public, relegated to being perfectly known and utterly passive, package-consuming consumers, with a gulf between us and an invisible state. Even more depressing, is there a clue of what has happened to that Dunkirk Spirit in the Deloitte article ? The ability to act together is thwarted, and here traded in for a fashionable medicalization of victimhood which vindicates each personal case but remains a reproach to what might have been. The authors report:

“Each of the five textile manufacturers that openDemocracy spoke to reported increased stress levels – sickness, repeated loss of sleep and raised anxiety – from knowing they could help, yet having their factories empty during the crisis.”

What about that “everyday story of country folk”, The Archers, which might have been relied on for national respite during lockdown? Instead it was simply withdrawn, only to ‘re-open’ as a sequence of ghostly interior monologues? Are we well on our way to what Varney wanted?

****

“Our great grand-children, when they learn how we began this War by snatching glory

out of defeat, and then swept on to victory, may also learn how the little holiday steamers made an excursion to hell and came back glorious.”

J.B.Priestley. ‘Postscript’ to the BBC news. June 5, 1940.

Another way of posing this question is to ask: where have all the Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsays gone? – the mastermind who pulled together the massive fleet of over 800 disparate vessels which during nine days ultimately saved 338,226 men from certain annihilation. That, of course, immediately brings you up short at the uniqueness of “one of the finest naval officers of the twentieth century” as First Sea Lord Sir Michael Boyce hailed him, along with the little mystery, frequently raised in modern accounts, of “why Ramsay has not received the public recognition he deserves.”

Delving further, these two points appear intimately connected. In 1935, after only four months, Ramsay had shocked his superiors by asking to be relieved of his duties as chief of staff to the commander-in-chief of the Home Fleet, Admiral Sir Roger Backhouse, whom he privately likened to Mussolini, when they fell out over how the fleet should be administered. Backhouse firmly believed in centralised control: Ramsay advocated for delegation and decentralization to better allow commanders to act at sea. But the very qualities which nearly torpedoed his promising Navy career, putting him on the Retired List by 1938 – “the stubborn self-assurance that he was always right, the impulse to circumvent authority and take the initiative” as Patrick J. Kiger describes him – made him a perfect fit for Dunkirk. He had sought Churchill’s help for reinstatement without success in 1937, but as war loomed in August 1939, Churchill appointed this by now “lesser luminary of the naval establishment” flag officer-in-charge, to shape up long-neglected naval operations at the British port of Dover.

According to Kiger, on May 19, 1940, a British government haunted by Gallipoli still regarded evacuation from the French coast across the English Channel as unthinkable. They “put some additional staff and 36 vessels, including civilian Channel ferries, at Ramsay’s disposal. That was all.” By May 22, the rapidly upgraded plan of the unthinkable drawn up by the War Office went up in smoke when Boulogne and Calais came under attack. Dunkirk was the only option left. Still, Ramsay was informed, they would delay the decision on evacuation for another two days. Having accepted a catastrophic loss of most of their army, the top brass in London now wondered if 45,000 men could be saved. Churchill was braced for “a colossal military disaster”.

Luckily, from May 20, Ramsay and his team had been doing what he did best: creating his own meticulous plan with the improvisational skill to alter it in real time, working the phones relentlessly, ignoring bureaucratic channels and slashing red tape. Four hours before he was finally given the official ‘go ahead’ on May 26, he “quietly started sending out the ferries from Dover and the small boats from Ramsgate Harbour, about 20 miles north, so that they wouldn’t get stuck in a cluster off the coast and become sitting ducks for German dive-bombers.” On May 29 alone, Ramsay rescued 47,310 soldiers, more than the War Office had envisioned for the entire evacuation. Even he thought the result was “beyond belief.” It enabled Churchill in his famous June 4 speech to claim that this retreat was the opposite of a capitulation, evidence of a national and imperial resolve that merited American support. No wonder he described it as a “miracle of deliverance.”

Churchill heaped praise on Navy and Merchant Navy command, and the industrial effort of the seven-day working week. Warming to his militaristic theme, he also warned the country that “we must be very careful not to assign to this deliverance the attributes of a victory. Wars are not won by evacuations.” There was no mention of the role of the civilian ‘small boats’ that ferried soldiers from the beaches to the deeper waters where larger ships waited for them. No acknowledgement that ‘Dunkirk spirit’ to this day marks the divide between the Phoney war and the “People’s war”, thanks to Ramsay’s ingenuity in unleashing a fantastic response from British people determined to save lives. That task was left to J.B. Priestley on June 5.

This is where my old school friend, Penelope Summerfield takes up the story in her fascinating account of ‘Dunkirk and the Popular Memory of Britain at War, 1940 – 58‘, to be visited in Part 3. And what is most fascinating about it is that from the beginning to the end of the contestation over the meaning of ’Dunkirk Spirit’, a contestation that arguably has not ended yet, the real row is over the role of the British people, class collaboration and people power.

****

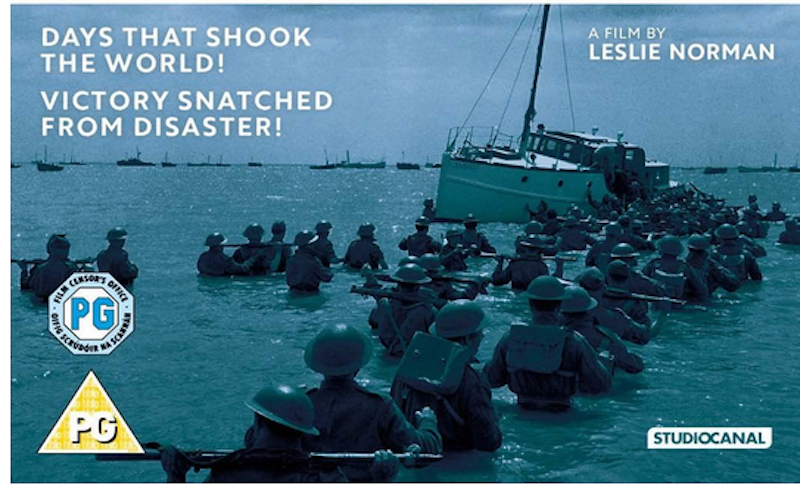

Dunkirk (1958). | Screenshot: [DVD cover]

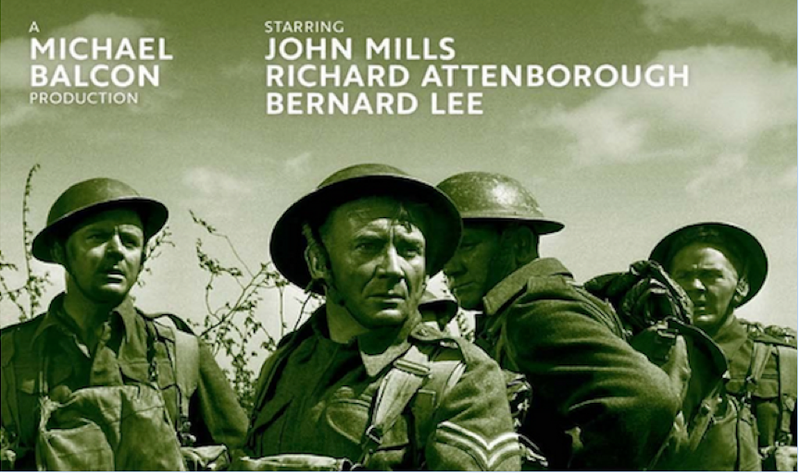

Dunkirk (1958). | Screenshot: [DVD cover]‘A study in cross-class consensualism; an enterprise which honours the group rather than the individual; and a war film which plays down heroics’ – Leslie Norman, Director, onDunkirk.

At the centre of Professor Summerfield’s complex and nuanced account of the two decades of contestation over the meaning of Dunkirk which saw it acquire “such a formidable position in national memory”, is the film, Dunkirk (1958).

To make this “the most important film in Ealing’s history ” Sir Malcolm Balcon, head of Ealing Studios, “struggled to achieve agreement about the representation of the evacuation.” The contestation hinged on whether or not “Dunkirk was to be remembered as an expression of the ‘people’s war’”, and it had begun “not in 1958 but in 1940”, with Churchill’s ‘fight them on the beaches’ speech on June 4, 1940, and JB Priestley’s first BBC Postscript on the following day.

Churchillian accounts in Times editorials and cinema newsreels portrayed the evacuation as a triumph above all for the Royal Navy, nation and empire. If the civilian crews in ‘Operation Dynamo’ received a mention, it was to insist on the subordination to naval command of the “motley collection of ships involved”.

This was in stark contrast to “the enthusiastic elaboration of small-boat rescue in a succession of wartime broadcasts, publications and films” kicked off by J.B.Priestley’s evocative Postscript, rather popular with the Americans whose support Churchill was wooing. Here the civilian contribution was given pride of place not only as a heroic victory, but as the threshold to the ‘people’s war’. Hollywood films like Wyler’s Mrs. Miniver, which topped British box offices in 1942, had a very different flavour from In Which We Serve, directed by Noel Coward and David Lean in the same year, where national unity was the product, not of voluntary civilian participation, but military and naval cooperation and the beneficial effects of social hierarchy.

Arthur D. Divine who published an influential eye-witness account of the evacuation entitled Miracle of Dunkirk in the mass-circulation Readers Digest, bridged the two positions, emphasising the overall control of the Royal Navy, but also praising the civilian boat owners. In 1956, it was Divine who replaced R.C. Sherriff, author of Journeys End (1928), as an accredited scriptwriter for Dunkirk.

Divine added a second civilian boat owner to the Dunkirk cast-list of foot-slogging soldiers which, consistent with Ealing’s ‘from below’ approach, focused on ordinary people “who converge on the sands of Dunkirk, where they learn something about themselves, the enemy, and the failings as well as the virtues of their own nation.”

The treatment set it apart from the hugely successful British war films of the 1950’s which sought to restore British military and masculine prestige after the Suez disaster of 1956. Dunkirk “placed masculine war heroism in a realist social context” using black and white film, into which they spliced wartime newsreel and documentary footage, supplemented with realistic reconstructions that required the considerable use of naval and military ‘facilities’.

Balcon also needed Army support for the Royal Premiere he wanted. All was nearly derailed in 1957, when the military adviser vetting the script for the Imperial General Staff declared that Ealing’s ‘from below’ strategy overemphasised “the chaos and the stragglers”, resulting in a “travesty of a major campaign.” Divine duly attempted to maintain his favoured status at the War Office by writing to distance himself from the script, in particular deriding the two civilians and the central character, Corporal Binns.

Nevertheless, after further reassurances and amendments, this intense exercise in synthesising conflicting narratives culminated in the film whose crowning glory is the working class Cockney Corporal Binns who becomes a leader of men on the road to Dunkirk. As played by John Mills with his unique ability as an actor to cross class boundaries – he had recently played a naval commander and an army captain – Binns is the ‘English everyman’ as a nation comes together, refusing to accept defeat.

“Will no one rid me of this turbulent Priestley?”

The BBC has an Archive on 4 which looks into Churchill’s role in “shoving” JB Priestley’s Postscripts “off the air”, as George Orwell put it, despite their drawing peak audiences of 16 million in the darkest days of 1940 and again in 1941, second only to the popularity of Churchill himself. Churchill let it be known that he, like many in his party, would like an end to the broadcasts, writing directly to the Minister for Information, Duff Cooper, that Priestley’s war aims were in fact “utterly contrary to my known views.”

What was it that so alarmed the Conservatives in 1940/41? We get a taste of Priestley’s anticipation of the Beveridge Report from his Postscript of October 6, 1940:

“We are at present floundering between two stools. One of them is our old acquaintance labelled ‘Every man for himself and the devil take the hindmost’… the other stool, on which millions are already perched without knowing it, has some lettering round it that hints that free men could combine without losing what’s essential to their free development, to see that each gives according to his ability and receives according to his need.”

Priestley was no communist. But his war aims were passionately spelt out in ‘A Plan for Britain’ in January 4, 1941, alongside other intellectuals and progressive politicians who set out the social and political changes they deemed necessary in employment, social security, planning, education, health care and leisure, if the land was to be fit for heroes this time around. Which suggests we might do no better than to turn, not to Christopher Nolan, but to Ken Loach’s The Spirit of ‘45’for the next tantalising sighting, flawed yet profound, of the Dunkirk promise.

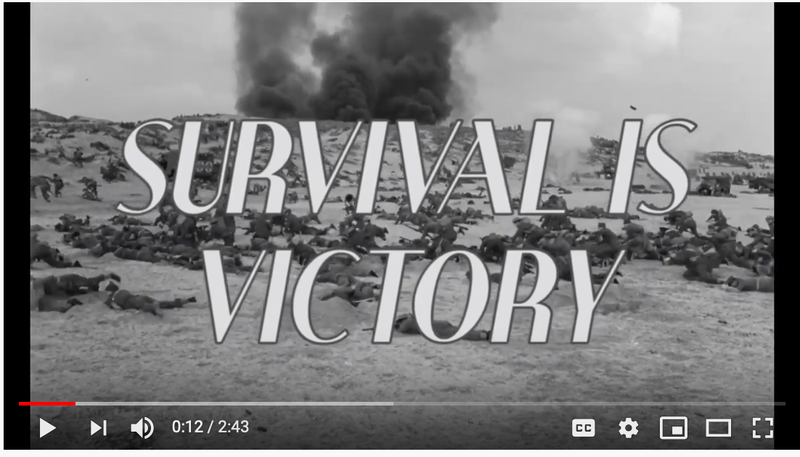

Dunkirk, film. (1958) | Screenshot.

Dunkirk, film. (1958) | Screenshot.CODA

Survival is victory! emblazons the Dunkirk trailer. Not Churchill’s idea of victory, however. Was this one of the factors precipitating his downfall in the 1945 elections? The spirit of ’45 went on to make some headway in creating a land fit for people. But Priestley’s “free men combined” were never institutionalised and without democratic control of the economy the people’s gains were gradually reversed. As we reassess Churchill’s career against the background of the pandemic, Dunkirk spirit, “cross class consensualism” and people on the ground are once again proving vital to saving lives, the NHS, our public health system. Once again this will be despite, not because of our leaders. Will we pull together in time to avert national disaster? As Professor Steve Reicher, behavioural psychologist, recently put it to the Independent SAGE meeting of July 24, 2020 (12.31 pm):

“The traditional view of crises is that in a crisis the public falls apart and acts irrationally and they need a good government to save them. So the public are the problem: and governments are the solution. I think we have seen precisely the opposite in this pandemic. We have seen remarkable resilience, remarkable mutual aid as we talked about earlier, remarkable compliance by the public coming together for the public good. And to a large extent they have been let down by a Government who haven’t acted in the same way.

I hope we learn from that, learn that in a crisis and in a future pandemic, actually the public aren’t the problem, they are the solution. And in building up policies, rather than talking down to the public, rather than not admitting your mistakes, we need to involve the public as a partner, we need to be open with them. We need to be transparent in our policies and we need in many ways to co-produce our reaction to the pandemic, as Independent Sage is trying to do.”

Screenshot: Dunkirk (1958). Leslie Norman, Director.

Screenshot: Dunkirk (1958). Leslie Norman, Director.This piece was originally published in the June, July and August editions of the Splinters column.

PrintRosemary Bechler | Radio Free (2020-08-04T08:06:28+00:00) Whatever happened to Dunkirk spirit?. Retrieved from https://www.radiofree.org/2020/08/04/whatever-happened-to-dunkirk-spirit/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.